Here are six sharp practices followed by new age startups:

#1. REDBUS

This bus ticket aggregator buys five seats in a bus with 45 seats. When four out of these five seats are booked on its app / website, RedBus flashes a warning saying “only one seat left”. I heard this directly from the horse’s mouth in the keynote address delivered by the founder of RedBus at a startup event many years ago.

This bus ticket aggregator buys five seats in a bus with 45 seats. When four out of these five seats are booked on its app / website, RedBus flashes a warning saying “only one seat left”. I heard this directly from the horse’s mouth in the keynote address delivered by the founder of RedBus at a startup event many years ago.

It’s quite possible that many of the other 40 seats outside the startup’s inventory are vacant but customers might miss that.

This is a canonical example of the False Sense of Urgency technique used very often in marketing. It’s one of the 29 Psychological Tricks To Make You Buy More.

It can be argued that, while RedBus creates a sense of urgency, there’s nothing false about it: When it says “only one seat left”, RedBus is referring to its inventory of five seats and the statement is true after four seats are sold out. However, when a consumer reads this message, they could conclude that there’s only one seat left in the whole bus and skip their careful purchase planning. Accordingly, this is also a classic case of obfuscation / plausible deniability.

#2. OLA UBER

Uber and Ola are known to snare drivers with attractive loans for buying cabs and then gradually reduce their payouts. Under pressure of loan repayments, drivers are unable to exit the network, and have to grin and bear it for as long as they can. With this practice – some call it exploitation – rideshare market leaders can improve their margins without risking the exodus of drivers from their platforms.

#3. OYO

When a hotel joins Oyo, the world’s largest budget hotel aggregator adds its listing to its platform. By that token, when a hotel signals its intention to exit the platform by terminating its agreement with Oyo, you’d expect the startup to drop the hotel’s listing from its platform.

When a hotel joins Oyo, the world’s largest budget hotel aggregator adds its listing to its platform. By that token, when a hotel signals its intention to exit the platform by terminating its agreement with Oyo, you’d expect the startup to drop the hotel’s listing from its platform.

But, no, Oyo doesn’t do that. According to the Economic Times article entitled Oyo’s layoffs have hotel partners worried, Oyo continues to display the hotel’s listing, but with a SOLD OUT tag on top of it.

The hotel owner is not happy because his rooms are not sold out and Oyo’s misrepresentation drives customers away from approaching the hotel.

However, Oyo can argue that, if a hotel exits its platform, it has zero rooms from the hotel. Since 0 rooms are always sold out, it’s not wrong in displaying the SOLD OUT sign.

This is another example of obfuscation.

Notwithstanding that, I refute the hotel owner’s claim that the customer is loyal to his hotel. Why the heck would a loyal customer of the hotel go to Oyo to find room availability in his hotel? Nobody who does that can be termed as loyal to the hotel.

This reminds me of crypto owners who were annoyed with Google after losing their coins. Instead of typing the URL of their wallet’s website on the brower’s address bar, they did a search on Google for the name of their wallet, clicked through the first one or two results, landed up on phishing websites, lost their cryptocurrency, and blamed Google for displaying ads by scammers.

My $0.02 to hotel users: Don’t whine about what aggregators do. Instead deepen your relationship with your customers so that they’re really loyal to you and prove that by coming to you directly instead of going to aggregator websites and apps.

According to recent complaints on social media, many people book a hotel on Oyo, make full payment, land up at the hotel, only to be told there’s no booking in their name.

Looks like hotel owners have decided to disengage with some customers but, who knows, maybe they followed my advice, made sure their loyal customers booked rooms with them directly, and are now left with no vacant rooms to allot to these disloyal customers.

#4. MAGICPIN

The founder of a leading restaurant chain recently complained on Twitter that Magicpin, a leading physical store discovery app, is taking reservations for his restaurants without their consent.

Hi @bhushan08 can you please help and explain to me, how and why is @mymagicpin taking reservations from our restaurants @bombaycanteen, Veronica’s without our consent or any legal contract/ partnership?

— Yash Bhanage (@yashwecan) July 9, 2023

The restaurant chain owner’s ask is not unreasonable.

As an angel investor in Ressy, a restaurant deals app, I also know that Ressy employs a team of business development executives who visit restaurants and get their consent before onboarding them on to its platform. AFAIK, even restaurant listing platforms like Swiggy and Zomato have partnership agreements with restaurants before they book their tables and deliver their food.

But I’m not sure if it’s necessary for an aggregator like Magicpin to have a prior agreement just to list its restaurants. Account aggregation PFM apps like Mint list all the 4500-odd banks in USA on their platform without any evidence that they have received consent from those banks. Ditto loyalty consolidators like Using Miles from the zillions of airlines whose loyalty programs they help passengers manage on their website. For all we know, listing restaurants without spending the time and money to strike partnerships with them could be the key differentiator and secret sauce of Magicpin.

Once a diner makes the reservation on Magicpin and visits the restaurant, she expects the restaurant to make the table available, so, at that stage, the startup surely must have an agreement with the restaurant to ensure availability.

Once it garners a critical mass of bookings for a particular restaurant, Magicpin might make an offer that the restaurant can’t refuse, thus ensuring availability of the required number of tables.

This is somewhat similar to the Cost Per Lead model. According to the grapevine, Direct Sales Agents (DSA) make spam calls to generate leads for personal loan, credit card, insurance and other BFSI products and shop around their leads with multiple banks and insurance operators. Some principals reject the lead because they had not appointed these DSAs to sell their products whereas others accept them and pay whatever is the going CPL rate. On a side note, this is one of the limitations of enforcement of DND.

Unfo such guidelines are virtually impossible to enforce if these calls are originated by an agent who can be disowned by the principal. Sure, RBI can shut down one agent – but that's like playing a whack-a-mole game.

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) April 21, 2023

Having said that, the restaurant chain enjoys copyright for its logo, menus and creatives and might be able to issue a DMCA takedown notice to Magicpin if the aggregator has scraped any of that content and reproduced them on its own website / app.

#5. SWIGGY

A tweeple complained that, when he canceled a (digital) payment on Swiggy, the food delivery app changed the payment terms to Cash on Delivery and processed the order.

Now Swiggy might argue that it automatically switched the method of payment from digital payment to COD in the interest of enhancing customer experience. Some diners might agree with that logic but others might find the practice too presumptuous and get annoyed.

When you cancel a payment on Swiggy, it still goes ahead & places the order, saying "You can pay with cash". Very slimy.

What if I don't have/ want to pay with cash or have decided to cancel anyway? You gotta get a customer to opt in for continuing with the order, not opt out.

— Ashok Lalla (@ashoklalla) May 30, 2023

On a side note, this dissonated with my experience – when I canceled a payment, Swiggy did not go ahead and place the order, via cash or any other MOP.

But digital apps have the ability to target features at a market segment of one. So, for all we know, what I saw on my phone is not necessarily the same as what the tweeple saw on his phone, and his reiteration of his experience could be totally genuine.

#6. SWIGGY AGAIN

Once upon a time, people hated minimum order values stipulated by restaurants for free home delivery. Ergo, when FoodPanda, Swiggy, and other food delivery startups entered the scene and offered delivery without any minimum order value, people gladly paid them delivery charges to be relieved of the restaurant’s minimum order value condition.

Once upon a time, people hated minimum order values stipulated by restaurants for free home delivery. Ergo, when FoodPanda, Swiggy, and other food delivery startups entered the scene and offered delivery without any minimum order value, people gladly paid them delivery charges to be relieved of the restaurant’s minimum order value condition.

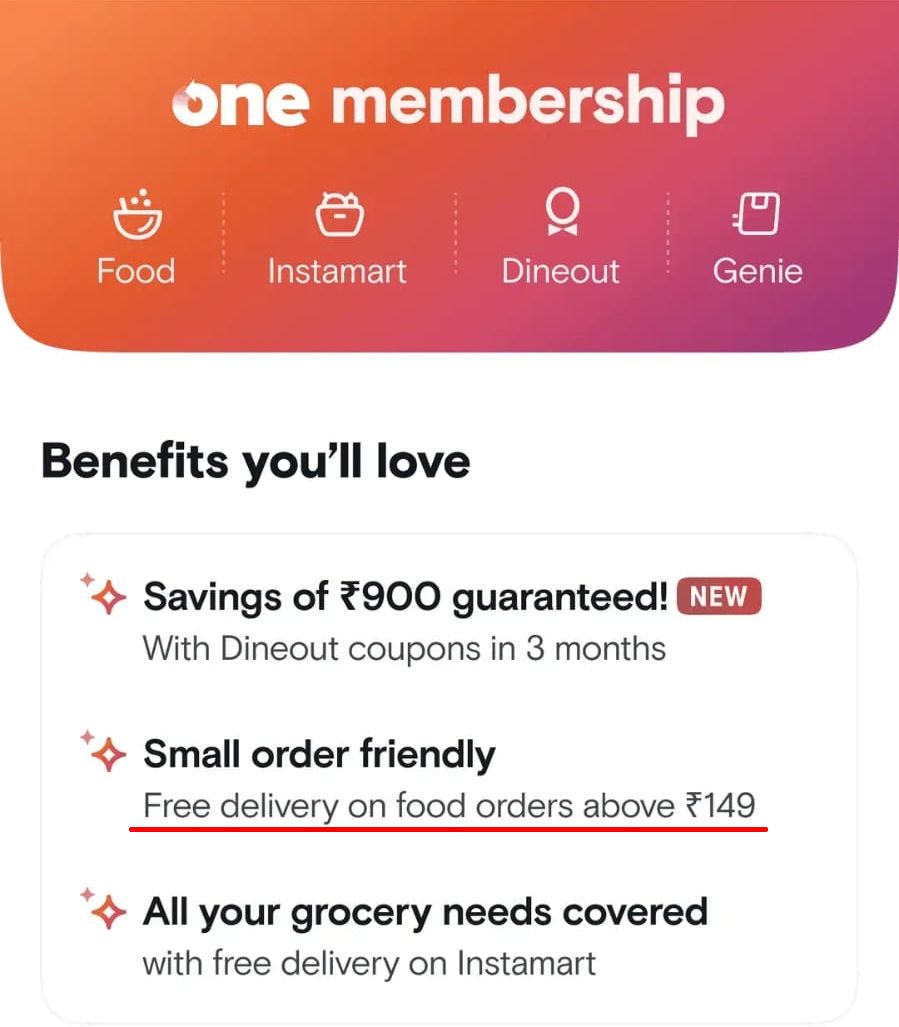

Over time, diners started feeling the pain of forking out delivery charges to these startups, who responded by introducing loyalty programs. Consumers pay a fixed fee – e.g. INR 999 for a year – to join the program and get free delivery in return. However, the free delivery under the loyalty program is available only for orders above a certain value.

I find it amusing that the very same consumer who resented the minimum order value condition from restaurants a few years ago is not only accepting the same condition from food delivery startups now but is also paying to be subject to the condition! Apart from Tech Kool-Aid, I can’t think of any other way to explain this paradoxical consumer behavior.

@gtm360: It’s easy to use Tech / Online / Digital as Kool-Aid to get Indian consumers to pull wool over their eyes compared to any other market I know.

But since I make my living by selling technology, I’m not complaining!

Most consumers would find something sneaky / cunning / dodgy about a majority of the above practices. Ergo I call them “sharp practices”.

Since nothing in this post is legal opinion or legal advice, I have no views on their legality or otherwise of these practices.

Let me hasten to add that sharp practices are not the sole preserve of new age startups.

In What Is Subscription Trap?, I’ve given several examples of old-age companies that use Roach Motel and other dark patterns to make it hard for people to cancel their subscriptions for their products / services.

Also, I’ve written about Feature or Bug practices followed by many old- and new-age companies here, here and here. Some of these practices might qualify to be called sharp practices.