The common man hears about Google Pay, PhonePe and PayTM while making UPI payments – rather than State Bank of India, HDFC Bank or ICICI Bank. Ergo there’s a widespread belief that banks have lost the UPI plot.

Take this tweet for example:

The statement on NEFT with stanchart applies to the HDFC as well.

UPI is doing well because (although not just because) banking UX is a hellhole inside a hellhole inside a hellhole. https://t.co/XNuphGWito

— Nikhil Pahwa (@nixxin) March 25, 2021

I disagree with this belief and replied as follows:

Well, UPI is also part of Banking! (For the uninitiated, UPI is run by scheme operator National Payments Corporation of India, which is jointly owned by leading Indian and foreign banks.)

To which the OP replied back as follows:

Well, it could be argued that the lacklustre performance of bank UPI services is a feature, not a bug, of payments industry! That’s what I’ll do in the rest of this blog post.

By transferring money instantly from payor’s account to payee’s account, Account-to-Account Real Time Payments like UPI eliminate float.

Since float is a key source of revenues for banks, you won’t find banks rushing headlong into A2A RTP systems anywhere in the world.

Where national A2A RTPs exist – that’s around 40 countries – they came about as a result of regulatory diktat.

India is no exception. The Indian regulator was easily able to achieve forced distribution of UPI among banks since 70% of the banking industry is owned by the government.

In UK, where virtually all banks are in the private sector, it took two years for the regulator to “persuade” banks to join FPS, the local version of A2A RTP, in 2008.

American regulator(s) have still not succeeded in this endeavor despite making persistent attempts for nearly 10 years. (It may be a good time to remind readers that there are nearly 4500 banks in America, all of them in the private sector.) That said, USA does have limited A2A RTPs like Venmo, Zelle, et al since several years ago.

Traditionally, Consumer Acquisition (acquiring of consumers who use payment cards and apps to make payments) is profitable for Banks but Merchant Acquiring (signing up of merchants to accept payment cards and apps) is a highly resource-intensive and low margin activity. This is true not only for payment systems like Debit Card with low-to-no Merchant Fees a/k/a Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) but also for ones like Credit Card that fetch banks 2-3% fees from merchants.

By maintaining the right mix of Credit Card (quite profitable), Debit Card (not very profitable) and A2A RTPs (not at all profitable) businesses, Banks have managed to optimize the profits of their payments business, taken as a whole. There’s a reason why I’ve said “optimize” and not “maximize” in the previous sentence. That will become clear in a bit.

Enter #ZeroMDR in India. According to this regulation that came into effect on 1 January 2020, banks can’t charge merchant fees for UPI payments. (The reg is not applicable for Visa and MasterCard payment cards.)

Latest status on scope of #ZeroMDR :

* Applicable for UPI, RuPay Debit Card

* Not applicable for Visa & MasterCard Debit Card & Credit Card

* ??? for RuPay Credit Card.https://t.co/dgJdYkcVqQ . pic.twitter.com/ju0urPJqri— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) August 17, 2020

Banks tried to compensate for the loss of UPI MDR by levying nominal charges on consumers for using more than a certain number of UPI payments in a month, but even that move got shot down by the regulator.

As a result, UPI has become a loss making proposition for banks.

The banking industry operates on the traditional PLBS model, where MSV is driven by revenues and profits. EPS is a key metric in this model and is subject to intense scrutiny by Wall Street and Dalal Street. Alarm bells will ring if banks miss their earnings estimates even in one quarter. All hell will break loose if they make losses and EPS becomes negative.

The banking industry operates on the traditional PLBS model, where MSV is driven by revenues and profits. EPS is a key metric in this model and is subject to intense scrutiny by Wall Street and Dalal Street. Alarm bells will ring if banks miss their earnings estimates even in one quarter. All hell will break loose if they make losses and EPS becomes negative.

Ergo, UPI customer acquisition and merchant acquiring have gone off banks’ radars.

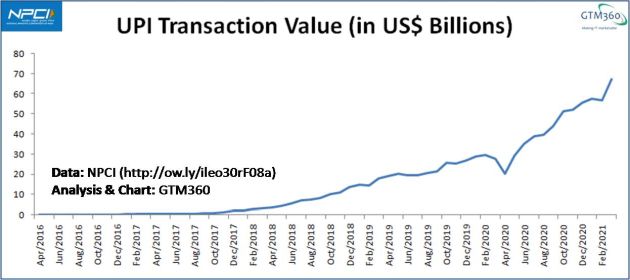

OTOH, UPI enjoys hockey stick growth because of a high population, disproportionately large number of micro and nano merchants (70M for a ~$3T GDP of India versus 8M for a ~$20T GDP of USA) and many other factors highlighted in Don’t Go Global Without Cracking The Value Proposition For Foreign Markets.

As a result, it tends to attract a lot of Venture Capital, as testified by the tons of VC funding raised by fintechs offering UPI front end apps.

Fintechs operate on the basis of the VC investment model, where MSV is driven by “capital gains” aka increase in the valuation of the fintech between successive funding rounds. Profit is not a key metric in this model, at least not in the short and medium term.

Allowed by their investors to make losses, VC backed fintechs spend truckloads of money to (a) acquire customers by giving cashbacks, and (b) enroll merchants by employing feet on street.

This is something that banks can’t or won’t do since, as we noted earlier, they operate on the traditional PLBS business model where profit is sacrosanct and loss is taboo.

But, due to regulation, banks can’t pull out of the UPI business either.

Stuck between a rock and hard place, banks have responded by limiting their exposure to the loss-making UPI business by ceding Customer and Merchant Acquisition to Fintechs.

That’s why you don’t hear about SBI or HDFC Bank or ICICI Bank while making a UPI payment.

I seriously doubt if UX of banking websites and apps has anything to do with this.

As long as fintechs continue to secure venture capital funding, they can remain aggressive in this space.

This nicely balanced model has been a win-win for everyone – as the burgeoning volumes and values of payments processed by UPI are testimony.

Except interoperability. More on that in a bit.

Now let me come to the part in the OP that seems to insinuate that banks will become “dumb pipes” by losing the customer and merchant relationships in UPI to third party apps.

The “dumb pipe” meme doesn’t hold much water in the banking industry, especially in a business like payments, which operates on multi-corner network model. Visa has no relationship with cardholders or merchants but is one of the largest financial services technology providers on the planet by revenues, profits and valuation. Ditto MasterCard and Plaid.

Whoa. I think Visa is also the most valuable finserv / fintech company on the planet. What I'd give to become a "dumb pipe". https://t.co/rSgsMwv8dM

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) December 15, 2019

Probably because they’re behind the scenes, the issuer and acquirer relationships owned by Visa (and MasterCard and Plaid) are often underrated in the popular narrative, but, perhaps more than anything else, they’re responsible for creating the much-reviled retail payments duopoly (and reportedly the US Department of Justice’s crackdown on Visa’s now aborted bid to acquire Plaid).

Meanwhile, Banks in India are doubling down on Visa and MasterCard credit card and debit card. Not subject to #ZeroMDR regulation, this business is still profitable and sits well inside banks’ PLBS model. See section titled “Wrest Control From Bureaucrats” in my blog post How RuPay Can Disrupt Visa And MasterCard for more on this topic.

I’m not for a moment claiming that that banking apps have great UX. In fact, I’ve said exactly the opposite many times in the past. Cf. my op-ed entitled “Impact of Regulation on Financial Service Providers” in the Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce for my take on this topic.

But UX has nothing to do with the position of banks in UPI. As we saw above, fading away from the UPI consumer app and merchant app league tables is a feature, not a bug, of the PLBS model governing the banking industry.

I posit that, even if banks magically overcome the UX challenges that I highlighted in Why Banks Will Never Catch Up With Fintechs On UX, they will not use their newfound UX mojo to compete with fintechs on UPI customer acquisition and merchant acquiring – unless #ZeroMDR reg is repealed.

Interoperability is a founding principle of UPI. It stipulates that anyone with a UPI app should be able to send money to anyone else having any UPI app by simply directing the payment to the recipient’s VPA (Virtual Payment Address) a/k/a UPI ID.

UPI’s founding fathers wanted the network to be open-loop.

Sadly, their noble goal has been given the short shrift in the way UPI has actually evolved in practice. Today, UPI is a panoply of many closed-loop wall gardens.

More on that in a follow-on post. Watch this space.

DISCLAIMER: This post is speculative and is the result of my connecting of the dots that I’ve seen in the public domain. It does not purport to provide any inside track into the thought processes, business plans or financials of banks or fintechs around UPI, except if noted otherwise. This post is not legal or investment advice.