This is a slightly edited version of my answer to the following question on Quora:

“We’ll disrupt uncouth taxi unions.”

“We’ll kill greedy banks.”

“We’ll upend shady realtors.”

Startups with noble mission statements like these get billions of dollars of VC funding and enjoy unicorn – or even decacorn – valuations.

As a result, the average entrepreneur tends to believe that VCs are major supporters of noble causes. Accordingly, some of them found startups to eliminate fake news, bring drinking water to everyone and solve the fundamental problems of the planet. When they go to VCs to raise funds, VCs are not impressed by them.

None of the above. VCs don't fund noble causes. https://t.co/ZJUvE9x606 .

https://t.co/tFbDDA7jBL— S.Ketharaman (@s_ketharaman) December 17, 2018

Then there are other entrepreneurs who pitch their startups as wholesome businesses that will grow steadily, pay dividends and become self-sustaining – in other words, operate like traditional business. VCs are actually depressed by them.

Take a leading VC, who makes his position very clear in his MEDIUM post:

the game has nothing to do with how good you are of an Entrepreneur (or) … with fairness. If you want to play, get rid of those notions.

The trick to impressing VCs is to understand the VC investment model and package a startup accordingly.

Ways to get funded (least fair to most fair)

🤑 Hot round/who else is investing

💼 Right school or resume

👣 Prior successful startup

👩🏻🔬 Actually novel breakthrough

🚀 TractionThe less you have of the first few, the more you have to get of the last two. It is what it is.

— Garry Tan 陈嘉兴 (@garrytan) October 21, 2018

Understanding the VC Investment Model

The seeds of venture capital were sown in the 1960s when 3M – one of my cult loyalty brands – set up an internal venture function to spot innovations from employees and provide “intrapreneurs” with a nurturing environment that’s removed from the redtape of a large organization. The goal for the inhouse venture capital division was to generate 30% of the company’s revenues from products that were launched in the previous five years. It delivered. Blockbuster products like Post It, Scotch Tape, and Scotch Brite are the creations of this division.

Dedicated VC firms cropped up not long after that.

Most of the VC action originated – and still happens – in Sand Hill Road in the Silicon Valley but VCs have been around in other parts of the world for a fairly long time. Memory serves, the first VC set shop in India in the mid 2000s.

Despite the fact that VCs have been around for decades, I’m amazed that many people don’t understand the VC investment model. Shockingly, this includes startup founders. In egregious cases of misunderstanding, founders believe that, since most VC-funded startups fail, the VC Model does not work.

Most people just don’t realize that failure of most startups is a feature, not a bug, of how the VC model works.

So, in an effort to change the status quo, let me give a quick overview of the VC model.

VCs raise funds from Limited Partners, who comprise pension funds, hedge funds and large banks.

The invest these funds in startups against a tacit promise of providing a return of around 20% IRR to LPs. That’s a lot of money considering that the 30-year U.S. Treasury Bond paid only 3% coupon rate in September 2018. It’s also a good 1000 to 1200 bps higher alpha than index funds.

(For those unfamiliar with IRR, Investopedia defines the term as follows: “Internal Rate of Return is a discount rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows from a particular project equal to zero.”)

VCs then invest these funds in startups.

From past experience, VCs know that 50% of startups will die (no matter what) and 30% of startups will barely manage to return their capital. Which means that VCs have to generate multibagger returns from the remaining 20%.

Since it’s impossible to predict upfront which startup will deliver how much returns, VCs invest in a portfolio of startups i.e. not just one startup. Question is how many and which startups.

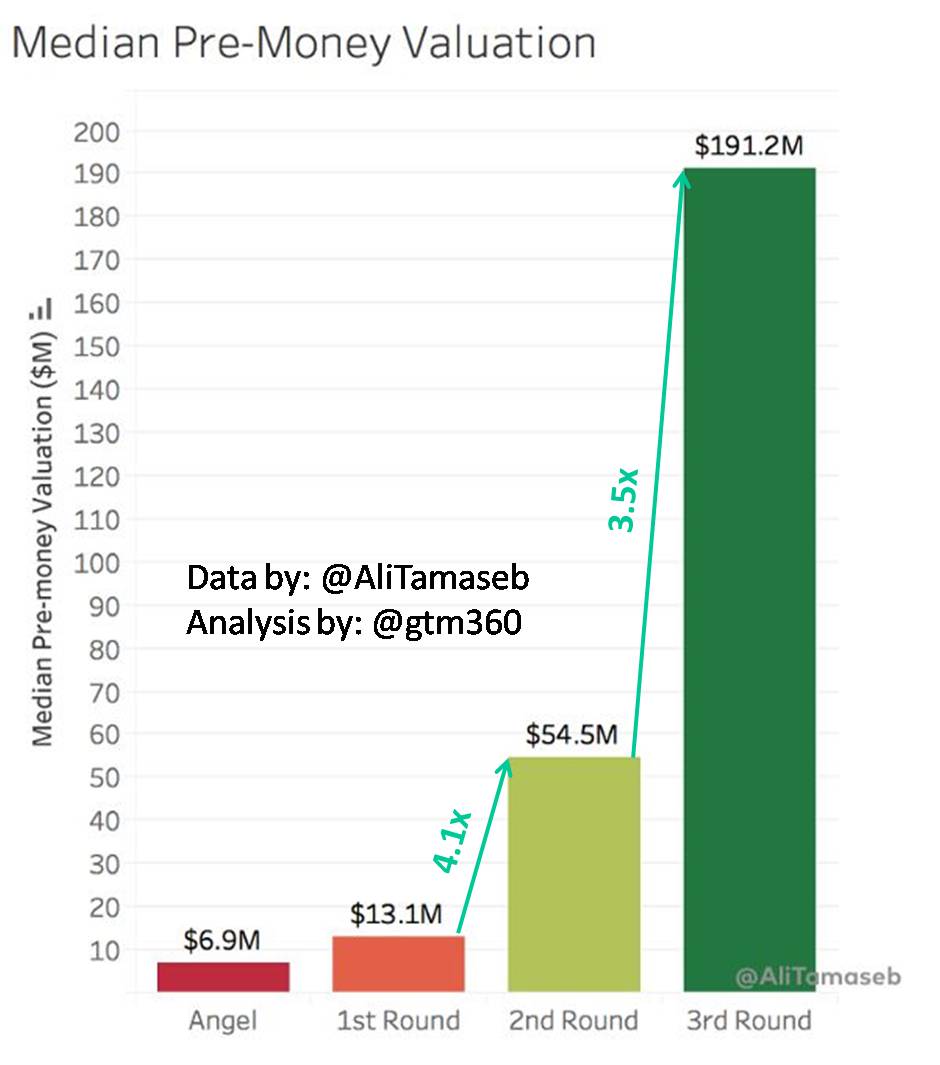

They buy equity in a certain funding round at a certain valuation with the aim of selling their stake (“exit”) at a much higher valuation in subsequent round(s) of funding in 18-36 months. To a common man, “much higher valuation” might sound delusional. But it does happen in actual practice, as this recent study of 195 unicorns stands testimony.

Accordingly, flipping stakes – and, at times, entire companies – is a feature, not a bug, of the VC model.

Some argue that this is not just the strategy but the purpose of the VC Investment Model. As Geoffrey Moore says in his article titled A Quantum Theory of Venture Capital Valuations,

The purpose of a round of venture funding is to get your company from one valuation state to the next”

The critical success factor of the model is to find startups that can attract multiple rounds of funding at ever-increasing valuations such that a VC who enters at one stage of funding gets the opportunity to exit with multibagger returns at a later stage.

Despite cash burn, Investors make record-breaking returns, Consumers get big discounts, Founders generate great wealth & Employees earn fat salaries.

Further proof that Cash Burn strategy works in VC model.

He who can understand that raises funds; he who can't fails.

— S.Ketharaman (@s_ketharaman) December 22, 2017

While wags wrongly deride this practice as “pump and dump”, this strategy has consistently delivered the highest returns of all asset classes over the past several decades (barring Bitcoin in the last decade).

The goal of VC model is to earn "Multibagger Returns in 2-3 Years". Some VCs like @letsventure overachieve it, other VCs underachieve it. But the goal does not change. #VC #VCModel pic.twitter.com/MJ4rvpYkid

— GTM360 (@GTM360) October 24, 2018

Interestingly, the valuation bump happens not just during the A through E series of the VC / PE model but even well after IPO. Take, for example, Dropbox, Snap and Tesla, three stellar public companies. All of them enjoy sky-high valuations despite making whopping losses.

Since a self-sustaining company will become cash positive, it will not go on raising external funds. Ergo, VCs are structurally incapable of profiting off of it. That’s why VCs are not interested in a profitable company, even though self-sustenance is the dream of traditional investors.

Not all startups will generate multibagger returns. Conversely, only startups with some traits will help VCs achieve their goal.

In a follow-on post, we’ll examine those traits and guide startups on how to package themselves for the VC Investment Model. Watch this space!