Amul and Parle have stopped supplies to Udaan. According to ET Prime,

Alleging that B2B ecommerce platform Udaan was monopolising distribution to retailers, some of India’s largest FMCG makers such as Amul and Parle have stopped supplying stocks to the startup.

Amul and Parle are multibillion dollar FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) companies headquartered in India and having global operations.

Billing itself as India’s largest B2B buying platform for retailers, Udaan buys fast moving consumer goods from manufacturers (such as Amul and Parle) and sells them online to retailers, which are mostly mom-and-pop stores (or khirana as they’re called in India). Udaan is India’s fastest unicorn – memory serves, it hit the one billion dollar valuation in seven months from inception.

Under normal circumstances, Amul and Parle should be treating Udaan as a channel partner.

But, at present, they’re sparring with Udaan.

Obviously, this is a strange development.

I don’t have a ringside view into this fight but let that not stop me from speculating about what’s happening behind the scenes.

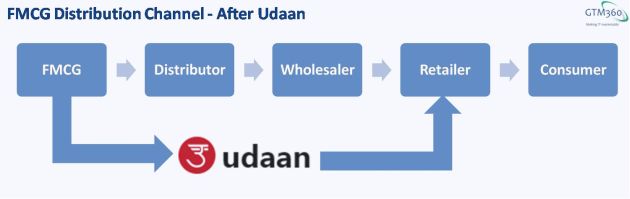

FMCG companies sell their products via distribution channel comprising distributor, wholesaler, and retailer. This is illustrated in the following exhibit.

Many distributors and wholesalers do hundreds of millions of dollars of business a year. Some of them are worth a billion dollars or more. But can you name a single distributor or wholesaler?

I thought so too.

Historically, the distributor and wholesaler ecosystem has been fragmented. As I highlighted in Decoding The Tenuous Link Between GDP And Payment Volumes, “Supply chains comprise small businesses. Anecdotally, there are 70M nano and micro merchants in India.”

As anyone who has been following the VC space would know, tech mediation of fragmented markets is a VC’s wet dream.

Udaan postured to use technology to disintermediate distributors-wholesalers and thereby offer lower prices (and deliver superior CX) to retailers. The post-Udaan distribution channel is illustrated in the following exhibit.

As we can see, distributors and wholesalers risk going out of the picture when Udaan enters the scene.

Like disruption stories in banking and other industries, Udaan’s proposition found ready acceptance among venture capital firms. They poured $280 million in a series of rounds within a few months to make the startup the fastest unicorn in India.

I’m guessing that Udaan kept prices low and funded the resulting losses with venture capital. That helped the startup to rapidly gain market share at the cost of distributors-wholesalers. My conjecture resonates strongly with the concern expressed by the sales head of a large FMCG company in the aforementioned article.

If B2B platforms like Udaan start supplying to retailers on cheaper terms, (this undercuts) … distributors.

On the supply side, FMCG companies started diverting a growing share of their supplies from their traditional distribution channel to Udaan. Apart from Amul and Parle, this included almost all large FMCG companies like Dabur, Marico and Nestle, according to ET Prime.

This caused the so-called “channel conflict”. A well-studied topic in FMCG and CPG distribution, it’s the jargon used to describe what happens when manufacturers bypass distributors and wholesalers and sell directly to retailers and / or consumers.

Of course, in this case, it’s not directly but via Udaan. But that nuance tends to get missed in all “killing the middleman” stories. Almost all Internet business models that claim to disrupt the middleman merely change the middleman – very rarely does the position of middleman disappear. The same has happened in this case. But, since the call to kill the middleman always enjoys strong Product Zeitgeist Fit with the hoi polloi, anyone who postures to do that becomes an immediate hero.

Far from killing the middleman as predicted, the Internet has created some of the biggest middlemen of all times e.g. Uber, AirBnB

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) November 30, 2016

As long as the market is growing, the overall pie expands, everybody has their share and nobody complains.

But that changed during the pandemic. India’s GDP cratered. The pie contracted. Distributors and wholesalers found their slice suddenly shrinking. They complained to FMCG companies.

Why should FMCG companies care? As long as their goods sell, why should they bother whether they’re selling via the traditional distribution channel or the new-age “Udaan channel”?

Honchos of FMCG companies are saying that they’re worried about what Udaan is doing to their traditional distribution channel.

(Udaan) hurts our partnerships with existing distributors.

Sorry but I don’t buy that.

When they started supplying to Udaan, FMCG companies consciously bypassed their traditional distribution channel. They obviously knew their actions would hurt their distributors and wholesalers. Still they went ahead and empowered Udaan, probably because they were drunk on the Kool Aid of technology disrupting B2B sales.

They’re also claiming that Udaan has become a monopoly in distribution to retailers.

If so, FMCG companies have brought this situation upon themselves. Unless they supplied exclusively to it, how could Udaan have become a monopoly?

(Udaan is not a monopoly but, for reasons we’ll see in a bit, it serves the interest of the FMCG industry to stick the monopoly label on the startup.)

Historically, FMCG companies have bossed around their distributors. According to rumors, many FMCG companies supply their fast moving products only if the distributor lifts a certain amount of their slow moving products in addition. In an egregious case of sheer dominance over the channel, one of the largest FMCG companies in India – the Indian subsidiary of one of the largest FMCG companies in the world – would demand that its distributors keep blank signed cheques at its factory gate; everytime it shipped a consignment to the distributor, it would write the invoice value on the cheque and bank it. It was least bothered how long it took the distributor to sell the goods and realize its payments.

Cue to the present day.

At its inception, Udaan postured to disrupt distributors and wholesalers. The posturing worked.

To whip up more froth and achieve the next level of valuation, I’m guessing that Udaan is now posturing to disrupt FMCG companies.

It’s a bold move, alright, but it’s not the first time that distributors / retailers have threatened to kill manufacturers:

- Amazon. The ecommerce giant has launched a wide range of private label brands that compete directly with the products sold on its marketplace platform by P&G and other FMCG companies.

- Fintech. At their inception, almost all fintechs used to posture that they’d kill banks with their shiny new apps and superior UX.

- Zomato. The food delivery decacorn has opened its own cloud kitchens, which will disintermediate the restaurants whose food it has been delivering all this while.

For the first time ever, FMCG companies are scared that they will get bossed around by their distributor aka Udaan. They’re trying to clip Udaan’s wings by cutting off supplies. Concern for traditional distributors – aka acknowledgement of channel conflict – is a smokescreen for self-preservation.

Nothing wrong about taking action to preserve oneself – that’s exactly how companies are supposed to respond in a free market.

Just that Udaan is claiming that it’s not a free market.

The startup has filed a complaint with India’s antitrust agency Competition Commission of India (CCI) against an FMCG company, alleging that it is abusing its dominant position by refusing to supply its biscuits to the startup. I don’t see how one biscuit manufacturer among hundreds can be so dominant as to invite regulatory intervention.

I also don’t get how Udaan is a monopoly when there are so many large players operating in B2B distribution e.g. cash-and-carry operations of of Metro (Germany) and Walmart (USA). In my opinion, FMCG companies are bandying about the monopoly word to seek regulatory intervention and thereby block Udaan from exerting hegemony over them or, worse, disrupt them altogether.

Both sides seem to be playing footloose with key business and legal concepts like abuse of dominant position and monopoly in a bid to shoot the other from the shoulders of the regulator.

I hope the regulator calls their bluff.

7 out of 10 people I asked didn't know the difference b/w "No MSG" & "No Added MSG". Hope the regulator who banned Maggi did.

— GTM360 (@GTM360) July 16, 2015