In Digital Ads: Whose Preference Is It Anyway?, we saw how digital ads are targeted on the basis of advertisers’ specifications regarding consumer preferences (“Meta Preferences“) rather than the consumer’s own preferences.

That speaks to the propriety of the advertiser to show its ads to a particular consumer.

But you might be wondering, just because an advertiser can show an ad doesn’t mean it should waste money by targeting its ads at disinterested consumers.

That’s a fair point.

In this blog post, we contend the following:

- In the case of non-discretionary goods, advertisers will only target interested consumers as far as possible.

- In the case of discretionary goods, advertisers will target all consumers.

Let’s get into it.

Nature of Goods

The notion of interest versus disinterest is shaped by the nature of products and services being advertised.

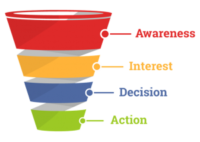

In the context of this post, the term “interest” means attention leading to purchase (rather than daydreaming) aka the Interest stage of the AIDA funnel shown on the right.

In the context of this post, the term “interest” means attention leading to purchase (rather than daydreaming) aka the Interest stage of the AIDA funnel shown on the right.

Products and services are classified as follows:

- Mandatory / Non-discretionary goods: These are products and services that are considered essential by consumers. Examples of non-discretionary goods include food, clothing, shelter, and so on. In this post, we’ll use the term “needs” to denote this category of goods.

- Optional / Discretionary goods: These are products and services that are considered non-essential by consumers but purchased if they have enough surplus income. Examples of discretionary goods include luxury car, overseas vacation, foreign education of children, etc. In this post, we’ll use the term “wants” to denote this category of goods.

As an aside, 20-40% of a country’s GDP comes from discretionary consumption. In poor nations, the figure is closer to 20% whereas, in rich nations, it’s closer to 40%.

Every consumer buys needs. Ergo the basic goal of advertising for needs is to influence brand choice, not so much to drive the purchase of the product per se (because that happens automatically).

But most consumers don’t buy wants readily even when they have surplus income. Therefore the basic goal of advertising for wants is to first remove the consumer’s inertia towards the product category and then steer her towards a specific brand.

“Capitalism requires the construction of needs that do not naturally occur”

– Martin Kihn, Gartner.

This in turn drives the basis of targeting of digital ads.

Targeting in Non Discretionary Goods

As far as possible, advertisers like to target their ads only at interested consumers because that not only enhances the customer experience but also prevents waste of their precious ad dollars.

The operating phrase is “as far as possible“.

In some types of digital ad platforms, it’s possible to know who is interested before starting the campaign.

Google Ads

Google displays ads to people who search for a certain keyword. The act of searching is widely believed to be a powerful signal of interest. Ergo, digital marketing professionals take painstaking efforts in selecting the right set of keywords for their Google Ads campaigns to ensure that their ads are only shown to people who have shown interest in their product / brand.

In some others, it’s not possible to know who is interested before starting the campaign.

Facebook Ads

As we saw in Part 1 of this blog post, Facebook lets advertisers target users by demographic and psychographic attributes as well as for having certain common attributes with the brand’s existing customers. Since these attributes don’t need to be related to the advertised product or brand, they don’t signal interest on the part of the users being targeted.

In still other cases, it’s not possible to get interest data at the start of the campaign and until midway through it.

User Input

Once a consumer sees an ad and clicks the Stop seeing this ad (in a Google Ads) or Hide Ad option (in a Facebook Ad), advertisers will take the hint and stop targeting her.

A relatively recent approach to sniff out interest is “Intent Data”.

Intent Data

Here’s a great example from MarTech of how that works in real life.

As a business journalist who’s reported on brand news for many years, … It used to be that any time I researched a brand I was reporting on, I’d get ads from them for months and months. (Now I don’t.) Analytics and insights on intent have finally gotten granular enough to rule out the case of the B2B news editor. Well done!

Here’s a guy who is aware of many brands and has shown interest by visiting their websites frequently. In the past, these brands showed him ads.

Now, they’ve realized that he has no desire to purchase their products and have turned off their ads.

This is awesome use of AIDA funnel data for ad campaign targeting.

This presents a classical conundrum in ad targeting. Even though the advertiser doesn’t want to target them, disinterested consumers will end up seeing the ads in all cases except the first.

The problem is exacerbated in modern times when, let alone assess the interest of consumers, it has become hard to even identify a given consumer because they now engage with a brand on a variety of devices like laptop, tablet, and smartphone.

Targeting in Discretionary Goods

As we noted earlier, no one is seriously interested in a discretionary product or the brand at first.

According to studies, it takes seven touches before a prospective consumer even registers a B2B technology brand – and many more for her to show interest in it.

Therefore, an advertiser will go out of business very soon if it restricts its targeting to only interested consumers (assuming it can even find out who is interested before the fact). See Sales Will Hasten Its Demise By Sitting On The BANT High Horse on a related topic.

Therefore, advertisers of discretionary goods will have to target all consumers.

Tradeoff between Privacy and Relevance

In both discretionary and non-discretionary goods, targeting of ads improves once the brand has gathered some data about customers.

I argued in Consent Dilemma – Have You Given It Or Not? that users have given consent to brands for gathering such additional data.

Whether anyone agrees with that contention or not, the bottomline is that there’s inherently a tradeoff between privacy and relevance.

As Marketoonist puts it well in the following cartoon, personalization can happen only if brands know more about the user.

In the absence of data, there’s no alternative to spam.

There are two ways by which brands can learn more about the user:

- Ask the user explicitly about her preferences via surveys, focus groups, and so on

- Infer the user’s preferences implicitly from her actions via algorithms.

Both approaches have their own pros and cons and regulatory ramifications.

(As an aside, in the case of B2B technology discretionary goods, #1 could be a fatal flaw, as I highlighted in Should You Ask Your Customers What They Want While Designing A New Product?).

Some brands / platforms will ask, others will infer, still others will do both.

Either way, in the Internet as we know it today,

You can either have more privacy (and reconcile yourselves to seeing spammy ads) or see more relevant ads (and reconcile yourselves to having less privacy), but not both.