In his op-ed entitled Tech What One Deserves in The Economic Times dated 17 July 2019, author Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar (@swaminomics) supports the move by governments of various countries to change the basis of corporate tax for tech startups from profits to sales.

According to @swaminomics, France has already taken the lead by levying a 3% tax on revenues of 30 digital companies with French revenues exceeding EUR 25 million.

Let’s examine the logic behind this move.

The basic tenets of income tax are place burden proportionate to the ability to pay and redistribute wealth to bring about more equitable development. In plain English, it means tax the rich.

Traditionally, profit has been the measure of a company’s richness, so it has been the valid basis for assessing corporate tax.

Profit continued to be an acceptable measure in the early stages of the digital economy when a startup took modest amount of money in its seed rounds to build a product, more money in its Series A round from VCs to achieve product-market fit and some more money in its Series B round to scale its operations. Startups achieved breakeven by later rounds of private funding and showed profits when they went public (Three consecutive years of profts is a prerequisite for getting listed on the Indian stock exchanges).

But profit is now “so 20th century”. As Kevin Roose observes in New York Times article The Entire Economy Is MoviePass Now. Enjoy It While You Can:

The new way to make it in business is to spend big, grow fast and use Kilimanjaro-size piles of investor cash to subsidize your losses, with a plan to become profitable somewhere down the road.

Many tech companies have adopted the “new way” and “somewhere down the road” has gone way past Series A.

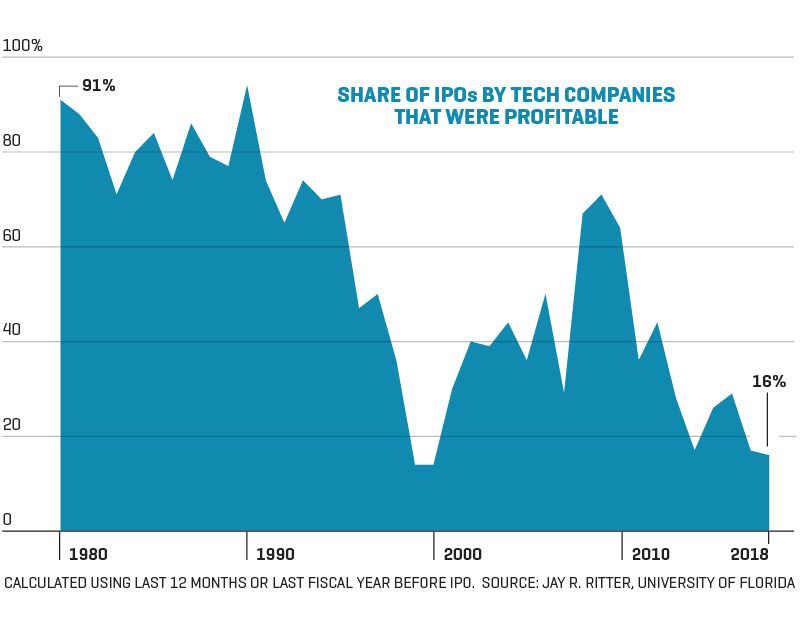

Fewer and fewer of them are profitable even when they go public. According to Fortune, the percentage of tech companies that were profitable at IPO has dropped from 91% in 1980 to just 16% in 2018 (in USA).

In other words, 84% of tech companies made losses at the IPO stage last year.

When a vast majority of tech companies make losses so late in their lifecycles, it means that the digital economy has disrupted the notion of profit.

It’s only fair for the taxman to respond by disrupting the notion of using profit as the yardstick for computing corporate tax.

Dropbox, Spotify, Snap, SurveyMonkey, Tesla … these are not the only startup-turned-public companies that enjoy skyhigh valuations despite making whopping losses. 83% of IPOs in 2018 were for loss-making companies. https://t.co/FWAE9InArz

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) March 5, 2019

It’s not only me.

Here’s what @swaminomics says on the topic:

Digital titans can show virtually no profits in the countries they serve … by vesting intellectual property rights with their headquarters … and arranging to have all subsidiaries pay high licensing fees for the IPR (aka royalty), thus transferring the bulk of profits to the HQ. To add to the problem, we have the new phenomenon of unicorns, new companies that … have market capitalisation of billions, yet run at a loss or marginal profit. These companies are well funded by fresh injections of capital and, hence, do not need to generate profits for growth. Here again, there is a case for levying a tax on revenue rather than profits.

It’s clear that profit is no longer a sensible basis for computing corporate tax.

But I’m not sure that it should be replaced by sales, as many nations are proposing, for at least five reasons:

- The innovative business models followed by digital companies have introduced many new metrics like Gross Merchandise Value, Gross Transaction Value, and Annual Recurring Revenue, all of which obfuscate the true sales figures

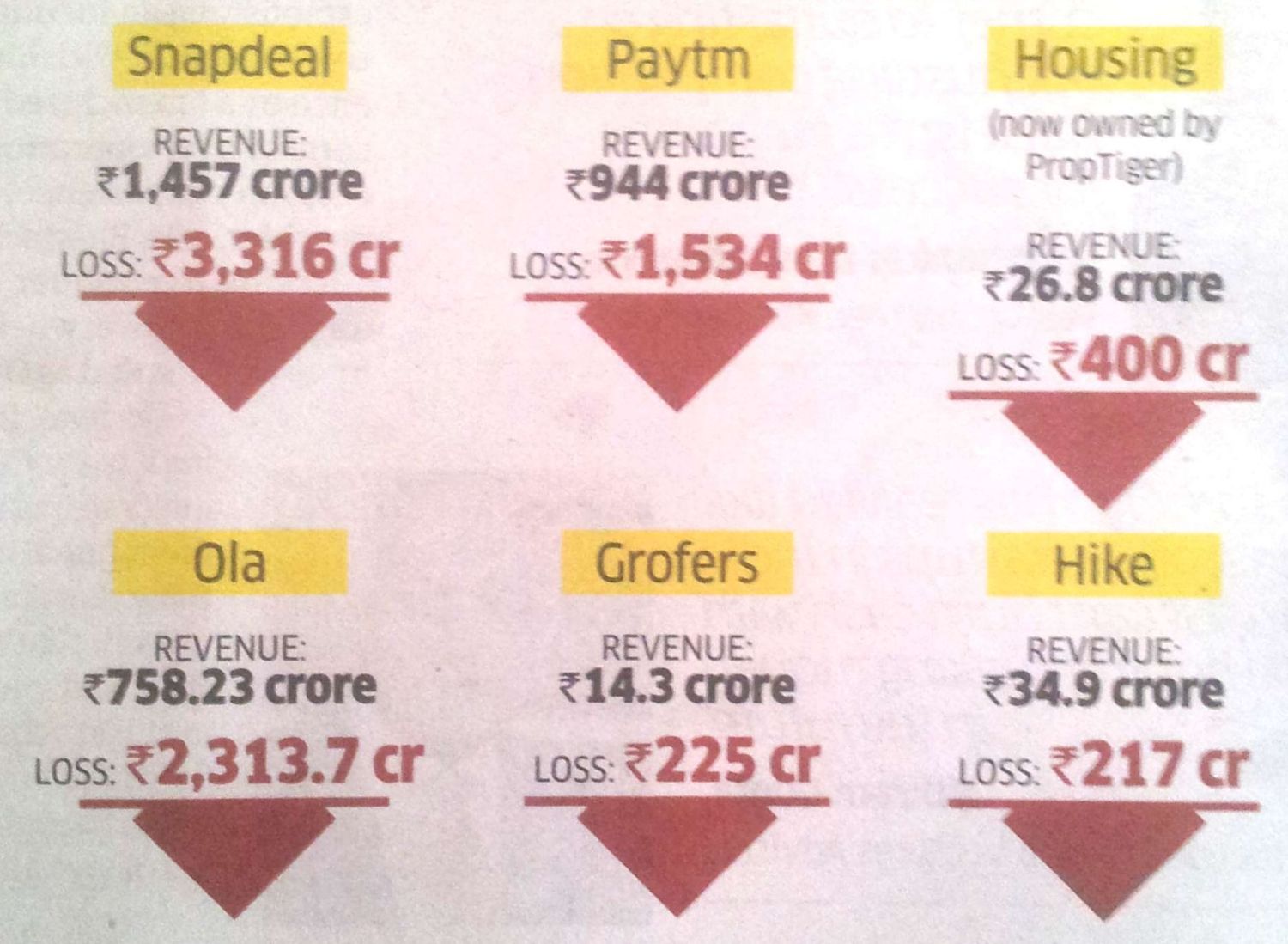

- Let alone profits, many new age tech startups don’t even make much revenues (unlike digital titans like Amazon, Facebook and Google)

- Pharma and other industries also pay royalty to their overseas principals, so it’s not only tech that follows creative accounting to choke profits

- Digital companies can pass on the tax on sales to customers as a separate tax line item.

- If the taxman does not permit that, digital companies can pass on it implicitly by increasing their basic price. Two things can happen in that case: (i) If their service is price elastic, their customers can respond by reducing consumption. In that case, digital companies will lose revenues but taxman will also lose tax (ii) If their service is price inelastic, consumption will remain unchanged, revenues will go up, taxman will gain tax but the jingoism of “We will tax Google” will not be accomplished – the end customer is the one who will bear the brunt of the tax.

Therefore, taxing sales will not fulfill the objective of the tax on tech startups.

Before I propose an alternative metric, let’s examine the case for taxing digital companies on any basis at all.

If many of these firms make losses and some of them don’t even make revenues, how can they be treated as rich and made liable to pay corporate tax?

The answer to this question will become clear when you consider the myriad ways in which digital companies enrich their stakeholders.

- Virtually every one of its portfolio companies runs at a loss, yet Softbank, the world’s leading VC / PE firm, is the 19th most profitable company in the world (Source: 2017 FORTUNE GLOBAL 500). Should you wish to understand the logic behind this apparent paradox, I recommend my blog posts When A Business Is VC Funded, VC Is The Business and If You Think VCs Create Bubbles, Meet ICOs.

- The founders of Flipkart pocketed a cool one billion dollars each from selling their stake in their company to Walmart. At the time, India’s largest e-commerce company had been in business for 10 years and had never made a profit or paid any corporate tax during this period

- It’s not only the blockbusters. The two founders of Snapdeal reportedly earn annual salaries of INR 50 crores (US$ 7 million) each despite making massive losses and overseeing a sharp fall in the valuation of their also-ran ecommerce company from 6 billion dollars two years ago to 100 million dollars today. Seven million dollars is a huge salary in any country

- It’s not just the big and the famous. From my personal experience as an angel investor, I know that promoters and employees in VC-funded tech startups earn way more than their counterparts in non-digital companies

- Fresh from funding rounds, startups use their largesse to splurge on things like office space and enrich landlords of commercial properties and other service providers in the process. (They also provide health insurance and other benefits to their employees but that’s not the point.)

It’s clear that, despite making losses (or marginal profits), digital companies generate a lot of wealth for their investors, promoters, employees and stakeholders.

So it’s right to treat them as rich entities and subject them to corporate tax.

When the regulators hear about how digital companies work, their kneejerk reaction is to tax investments as income (à la Angel Tax), impose ceilings on royalty, threaten to control discounts, and so on.

IMO, that’s old school thinking. For one, the government shouldn’t be preaching how a private sector company should be run. For another, the tax department doesn’t collect any new tax with this retrograde approach, so it defeats the basic purpose.

According to me, the tax man should adopt a modern approach.

Digital companies keep talking about how they innovate new business models and disrupt the status quo.

The tax department should do the same.

They should disrupt the prevailing notion of treating profit as the basis of taxation and innovate to find new ways to redistribute wealth, which is the purpose of income tax.

It is no secret that funds raised by digital companies in successive rounds of investments from ever increasing valuation is the source of their richness despite losses.

So, IMO, valuation may be an apt basis to assess corporate tax on tech startups.

I suggest a Valuation Tax, a tax levied on the valuation gained by a digital company during a year.

Valuation Tax is a very simple and transparent tax. It’s based on publicly disclosed numbers and does not require the taxman to poke his nose too deeply into a company (unlike Angel Tax). It also leaves valuation to market forces, where it belongs.

Valuation Tax is also inherently fair – if a company can become rich off of valuation, so should the tax department.

As Milo Minderbinder, my most favorite fiction character from Catch 22, would say, valuation tax ensures that “everyone has a share”.

I wrote a letter to The Economic Times along the above lines. It was printed in the ET edition dated 18 July 2019.

Here’s the as-published version of the letter.