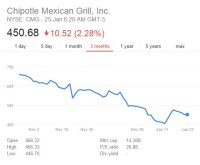

Following Chipotle’s e-coli scare late last year, the burrito chain’s stock has been on a free fall. From a peak of ~$750 in October 2015, the stock price plummeted to ~$400 at the height of the crisis last month. At the time, it was rumored that the company might be forced to file for bankruptcy.

Whether the rumor is true or not, banks will know Chipotle is going bankrupt before Chipotle’s CEO.

How?

Because they’ve been tracking footfall at Chipotle’s outlets from the space. Yeah, that’s right. From. The. Space.

This data is made available by Orbital Insight, one of a new breed of companies that gather data from the space by floating low earth orbit satellites.

This is not all: According to a recent article titled “Traders’ New Edge: Satellite Data” in Fortune, Orbital Insight “also zeroes in on the parking lots of more than 50 U.S. retailers, providing intel about store traffic to hedge funds and other investors.” So the investment community will know whether a retailer’s sales will rise or fall before the retailer.

These examples show that, when it comes to making a quick buck, financial services follows a “no holds barred” approach towards gathering and analyzing data. Even from above the earth.

Now, when it comes down to earth, many finsurgents claim that traditional banks, financial services and insurance companies do little to analyze the petabytes of data they have about their customers’ spending habits. This doesn’t resonate with my personal experience and anecdotal evidence:

- A bank made a snap offer for mortgage when I encashed my fixed deposits to fund a house purchase (click here for more).

- Cardlytics claims over 500 banking industry customers in USA for its credit card spend analysis technology.

However, that’s not the point of this post.

I’m more interested here in understanding how brands – in BFSI and other industries – can translate data-based insights into customer engagement actions. I realized the challenges involved in this process when I chanced upon the following tweet:

Visited a PvtClinic. Dr prescribed meds.Got an SMS from dotcom company that they'll deliver on discount. Is there something called privacy?

— Rajagopal CV (@rajagopalcv) January 19, 2016

This is a great example of a brand using analytics to make a highly relevant offer and, that too, in real time. As a marketer and CX advocate, I’d laud the private clinic and the drug company for reaching out to @rajagopalcv to help him save money (by offering a discount) and make his life convenient (by offering home delivery) before he went in search of a pharmacy and bought the medicines at full price.

However, as the consumer, does @rajagopalcv share my view? No. Instead, he’s peeved about the loss of privacy and has ignored the offer.

Lest we explain his outburst on the grounds of data privacy, I’ve visited a few private healthcare providers. Each of them asked me to sign a form in which there was an opt-in clause to the effect, “I agree to receive communications from our authorized partners”. Based on my personal experience, I’m quite sure that @rajagopalcv would’ve similarly given his consent for allowing the private clinic for sharing his data with third party companies. (NOTE: In the absence of HIPAA-like health data protection laws, a patient’s consent is deemed adequate for disclosure of health information in India.)

So, technically, this guy shouldn’t be cribbing about getting this targeted offer. Despite that, he does. That too, in public.

He’s not alone. A couple of friends and family members whom I quizzed sided with him and said they’d also be ticked off under similar circumstances.

So, even when they opt in, consumers don’t necessarily welcome relevant and timely offers.

Right or wrong, logical or illogical, this is consumer behavior. Brands ignore such vagaries and vicissitudes of the market at their own peril.

The problem is exacerbated when brands deal with sensitive information related to a consumer’s finances as those in BFSI do. And involves issues that go beyond the realm of technology.

Before going further, let me recast the above offer in the context of retail banking as an example of BFSI:

You close a mortgage with a bank and receive a discount on home furnishings from a leading retailer.

Assuming that you checked a box in the mortgage application to receive offers for third party products, here are some questions to which I’m seeking answers:

QUESTION 1: Would you feel better or worse that the bank has shared your financial information with a third party?

QUESTION 2: Should the bank ignore complaints – à la @rajagopalcv’s – and continue to make more targeted offers? (After all, I claimed that Winners Incite Action. Losers Wait For Actionable Insight and will excuse banks for not wanting to be losers)

QUESTION 3: Should the bank take the safe way out and stop sending targeted offers altogether?

Please let me know your thoughts in the comments box below. Thanks in advance.

UPDATE DATED 18 AUGUST 2018:

Two years after I published this post, banks seem to have ignored potential complaints and gone ahead with making targeted offers. According to Bloomberg, Cardlytics now has 2000 bank customers and mines $1.5T worth of purchase data to suggest targeted offers to its bank partners. Here’s an example of such a targeted offer from this article:

“Cardlytics might identify active travelers based on their spending on hotel stays and airline purchases and work with merchants such as Airbnb Inc. to deliver them an offer.”

Bank partners have collected $175M from Cardlytics for the privilege of sharing purchase data with Cardlytics. Which doesn’t sound like much until you realize that the bigger draw for banks is customers’ increased use of their cards, from which they got a boost of 9 percent.