Like many countries, India has a withholding tax regime. Called “Tax Deducted At Source”, the withholding tax is applicable on salaries paid to employees, commissions paid to agents, rents paid to landlords, professional fees paid to service providers, and many other types of B2B and B2C payments.

In this blog post, I’ll dive deeply into TDS on the last type of payment, in which a company (“Customer”) pays its chartered accountants, lawyers and marketing agencies (“Supplier”) for purchase of professional services.

Technically, the Supplier is liable to pay Income Tax to the Government. To accelerate collection and to improve tax compliance, the Government uses the TDS mechanism and directs the Customer to deduct the Income Tax due from the Supplier (TDS) while settling the Supplier’s invoice.

The Customer pays the invoice amount less TDS to the Supplier and must remit the withheld TDS amount to the Government by the fifth day of the following month. Customer makes the remittance to the Government via the Tax Department’s TDS website and provides the Supplier’s PAN # and Deductee ID in its quarterly TDS Return filed subsequently.

When the Supplier files his Income Tax Return, the Tax Department’s IT portal will reflect the TDS amount deducted by his Customer and he’ll be required to pay only the Net Income Tax due from him.

The end-to-end TDS cycle is illustrated in the following exhibit.

This process works as advertised as long as the Customer remits the TDS to the Government and files his TDS Return correctly.

Quite often, these two things don’t happen on time or at all.

Many Customers either (A) delay the remittance of TDS to the Government, or (B) make mistakes while entering the Supplier’s particulars while filing their TDS Returns. As a result, the Government does not receive its due from the Customer.

The Supreme Court of India has ruled that the Supplier should still be held liable to pay only the Net Income Tax, and that it’s the job of the Income Tax Department to chase up with the errant Customer to recover its dues. This is only fair to the tax payer.

However, in actual practice, Court proposes but software disposes.

When the Supplier logs on to the IT portal to file his IT Return, he doesn’t get credit for the TDS he has already suffered. This happens because the IT portal hasn’t received this information from the Customer, who hasn’t filed his TDS Return at all or has filed it incorrectly.

Accordingly, the IT portal tells the Supplier to pay the Gross Income Tax. Since the Gross Income Tax is higher than the Net Income Tax that the Supplier really owes, the Tax Department’s demand is patently unjust.

This causes a double whammy to the Supplier’s cash flow because not only was he shortpaid by his Customer but he also now needs to fork out the shortfall amount to the Government.

However, the Supplier has no choice: The way the software is written, he has to pay the Gross Income Tax before he can complete the filing of his IT Return.

To summarize, the Supreme Court holds the tax payer liable only for the Net Income Tax, but the software flouts the SC’s ruling by compelling him to pay the higher amount of Gross Income Tax.

A human being or a body corporate will be held in contempt of court in such a situation.

Software is supposed to be eating the world, which includes human beings and body corporates, so IMO software should also be held in contempt of court.

In the above example, the software’s owners are readily identifiable. Should someone wish to seek redress for the software’s unruly behavior, it’s easy to figure out whose throat to choke. It’s also easy for the software to conform with the law if its makers enhance it to accept TDS details from Suppliers along with proof that they have suffered the claimed deduction. In short, it’s easy to identify and sue the software’s owners.

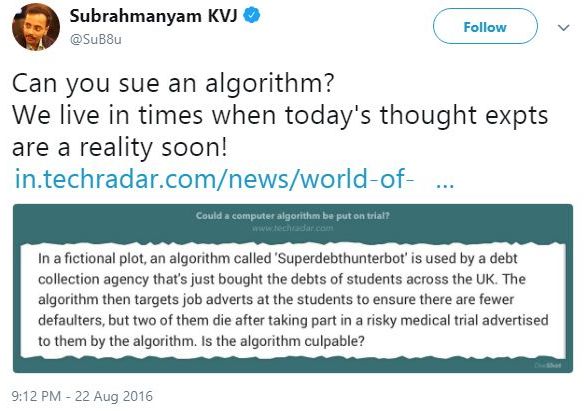

But the same can’t be said for the emerging world of AI / ML and Blockchain software.

- How do you sue an AI / ML algorithm when its creators can’t definitively explain why the software took a certain decision?

- How do you sue a Blockchain distributed application (dApp) when it is not controlled by any centralized entity?

These are interesting questions for which I have no ready answers. I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

PS: Legal language uses “his” to refer to companies as well as both masculine and feminine genders. Given the context of this post, I’ve adopted the same convention.