Once upon a time, the best way to discover places in a new city was to jump into a taxi and ask the driver to take you around.

Gone are those days.

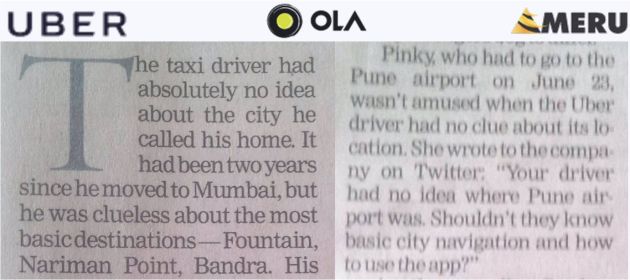

In the era of ride hailing cabs like Uber, Ola, Meru, et al, your cabbie may know far less about the city than you. (Quite similar to stepping into an electronics store and asking the salesperson about features of the latest model of laptop or smartphone.)

In the era of ride hailing cabs like Uber, Ola, Meru, et al, your cabbie may know far less about the city than you. (Quite similar to stepping into an electronics store and asking the salesperson about features of the latest model of laptop or smartphone.)

I live in Pune in Western India. Like in most Indian cities, M.G Road (after Mahatma Gandhi) is a prominent road in Pune. Usually anyone in the city would know where it’s located. But not my Uber driver.

Not just this prominent road – I’ve been on Uber and Ola cabs where the driver didn’t know localities like Kalyaninagar and Koregaon Park.

And it’s not just in Pune.

A Meru cab driver in Mumbai hadn’t heard about Tardeo, a prominent neighborhood in South Mumbai.

On a recent trip to Chennai, a city in South India, I had a few hours to kill before my appointment in the evening. I decided to go down memory lane and booked an Ola Rental at the airport to visit my old school. It’s located in a prominent locality called Mandaveli. The cabbie didn’t know where Mandaveli was situated. Although I hadn’t been to the school since I left it in the early 1970s, I remembered enough of the place to be able to reach it.

I got the ultimate shock in Bangalore, another city in South India. As soon as I entered the Ola cab in the Tin Factory area, the driver told me, “No English, No Hindi, No Bangalore”, making it clear that I’d need to give him directions to my destination (JP Nagar) in the local language (Kannada).

Since I neither knew JP Nagar nor Kannada, I punched in my hotel’s address into the driver’s Google Maps and handed his smartphone back to him. We reached the area uneventfully but it took 20 minutes to navigate the “last mile” to the hotel.

And it’s not only me.

Many people regularly complain that their rideshare drivers didn’t know equally prominent places in their cities.

Contrast this with traditional cabbies who need to clear a test to get a taxi permit from the local government. The Knowledge Test in London requires cabbies to learn 320 routes through 25,000 streets by heart. While I don’t know of any mandatory test in India, traditional cabbies do know the city – or at least their part of the city – inside out.

But, despite struggling with directions, app cab drivers somehow take their passengers to the desired destination.

Lack of drivers’ familiarity with local topography is not the only way in which the rideshare industry goes against conventional wisdom.

I can think of at least two more areas of disconnects:

- Extreme dependence on mobile network coverage

- Eschewing of branding

As we all know, unlike conventional yellow top taxis, rideshare cabs don’t have a meter. The driver’s smartphone app uses GPS to track the route and clock to track the time of the journey. At the destination, the driver swipes the End Trip button on the app. The app sends the route and travel time to the server over the air. The server sitting in the cloud computes the fare and communicates it back to the driver’s smartphone.

As a result, the whole rideshare model depends on robust network coverage all over the city.

We all crib about frequent call drops and Internet outages in many parts of any city. So, according to common wisdom, the aggregator cab model should break down frequently.

But, it does not. Regardless of where you go, the driver’s app manages to access the network and find out the fare. In the very rare occasion that it does not, the driver can call the rideshare company’s call center and get the fare – this has happened to me only once in the 200+ rides I must have taken in the last 3-4 years. That’s, like, 99.5% success rate.

I'm guessing Uber has 1000s of top riders of the week per city. Does anyone have a more definitive figure? pic.twitter.com/EpN0GpQfj5

— GTM360 (@GTM360) April 14, 2017

Take another common wisdom: Brand identity is very important, especially for consumer-facing companies. Consumer products sport the logo of their brands prominently.

But not aggregator cabs. Very few Uber / Ola taxis display their respective logo. Apparently, most of their drivers choose not to display the logo so as to hide their presence from regular taxis and auto rickshaws, who protest against cab aggregators for encroaching on their turf and, that too, without any government taxi permit of the type – à la NYC Taxi Medallion or London Taxi Driver License – required by traditional cabbies.

Still you always manage to find your Uber or Ola cab.

Despite going against the popular narrative in so many ways, rideshare startups have created a multibillion dollar industry.

How?

I attribute the success of ride hailing to the superior use of digital technologies by the industry viz. Mobile, Analytics, Cloud, Social.

Mobile: The rider and driver frontends work on mobile app. By making heavy use of turn-by-turn navigation on mobile devices, the rideshare model has virtually removed the need for cabbies to know the local topography.

How much money do Uber, Ola et al pay Google to use Google Maps?https://t.co/YVZJqgOwTq

— GTM360 (@GTM360) October 5, 2016

Analytics: I’ve pointed out many examples of use of sophisticated analytics technology by Uber in Mastering Targeted Offers – The Uber Way and Uber Masters Abandoner Remarketing.

Cloud: The entire platform is based on the cloud. Enough said.

Social: All ride hailing companies make extensive use of social networks for marketing and customer support.

There's a remarkable improvement in Uber's support since I wrote https://t.co/1x5GVherAk. #CorrelationOrCausation?

— GTM360 (@GTM360) September 5, 2017

Ergo, rideshare is a great testimonial for a digital business.

Technology also plays a vital role in the business model of rideshare.

From what I’ve observed, cab aggregators have rolled out their business model in the following phases:

- Phase 1: Pay ₹2600 to drivers for staying logged in to the network for 14 hours (“show up”)

- Phase 2: Pay ₹2600 for doing 14 rides

- Phase 3: Pay ₹2600 for billing ₹2600 (“eat what you kill”)

- Phase 4: Alert drivers that company will eventually levy a commission but not charge it

- Phase 5: Turn on a switch in the software to start charging 15% commission.

(Actual figures may vary slightly from city to city)

At every stage, technology has been used for communications and to monitor and measure operations.

In the last phase, with a mere flip of a software switch, ridshare startups generated revenues from commissions and created a billion dollar business overnight.

This is not to say that technology is the only secret of success of cab aggregators. I’ll cover two more critical success factors of this business in Part 2. Watch this space!

UPDATE DATED 5 OCTOBER 2019:

Revenues, yes, but rideshare startups haven’t been able to flip a switch to generate profits. In its IPO filings, Uber warned that it may never make a profit.

"Uber Warns It May Never Make Profit".

We'll know when Uber's IPO opens next month whether the common man has taken this as a warning or bragging! pic.twitter.com/3tKsfcFNCJ— GTM360 (@GTM360) April 24, 2019