This post provides a quick primer on MDR, Interchange, and Surcharge, and covers a few recent updates to rules around these key concepts in the credit card industry.

1. Merchant Discount Rate (MDR)

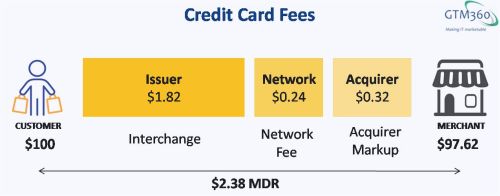

When you buy something worth $100 and pay with a credit card, the merchant gets $97.62.

The difference of $2.38 is the fees paid by the merchant for using the credit card network to receive payments. It’s called Merchant Discount Rate (MDR) or Merchant Service Charge (MSC). Spec’ced by the card networks (e.g. Visa, MasterCard), MDR varies from one class of credit card to another and across different merchandise types but averages 2.38%.

2. Interchange

While MDR and Interchange are related, they’re not the same:

MDR = Interchange + Network Fee + Acquirer Markup.

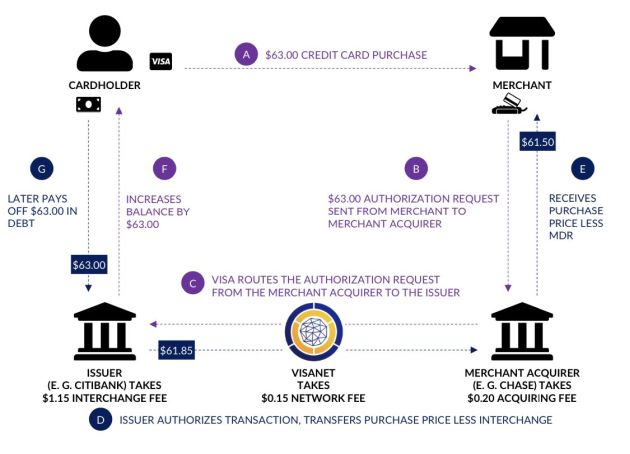

Because Visa, MasterCard, and other card networks set interchange rates for their respective networks, the common man – and some self-styled experts – think that they receive the interchange revenue. That’s not true. Interchange goes to the Issuer Bank (the bank that has issued the credit card to the consumer), which then distributes a small portion of it as network fee to the Card Network and acquirer markup to the Acquirer Bank (the bank that issues the merchant account / POS terminal to the merchant and thereby enables it to accept credit card payments).

This is easy to verify: The Total Payments Value of Visa credit card transactions was $8 trillion last year. 2% interchange on that TPV works out to $160B. Visa’s revenue was $30B.

@s_ketharaman: PSA for Faux Patriots: Visa / MasterCard don’t earn ₹2 on every ₹100 credit card transaction in India. They earn only ₹0.25. The other ₹1.75 is earned by banks in India who pay tax due on it to Indian govt, India benefits. OTOH, banks in India make ₹0 on a typical ₹100 UPI payment, pay no tax, nation does not benefit, on the contrary government pays subsidy from taxpayer money to banks to compensate them for processing UPI payments without charging any MDR.

In the above example, out of the $2.38 MDR, issuer bank gets $1.82 (Interchange), card network gets $0.24 (Network Fee), and acquirer bank gets $0.32 (Acquirer Markup) to the acquirer bank. This is illustrated in the following exhibit of the credit card value chain:

3. Why MDR Is Ad Valorem

Since the technology for processing credit card has a fixed cost, the J6P (Joe Six Pack) wonders why banks charge an ad valorem fees of 2.38% instead of a fixed amount independent of the sale value. In other words, why should MDR be different for $10 versus $1000 credit card payment?

To grasp this apparent disconnect, it’s necessary to go beyond technology and understand pricing models and the product concept of credit card.

My immediate reaction is, so what if the cost of processing the $10 and $1000 payment is the same? In a free market, the issuer bank should be free to charge whatever it wants (and the merchant should be free to take it or leave it). There’s nothing sacrosanct about price being proportional to cost – there are many pricing models. “Cost Plus”, where higher the cost means higher the price, is only one of them. But there are others like “What the Traffic Can Bear” where price is not necessarily in direct proportion to cost. (More at Resolving The Tussle Between Different Pricing Methods)

Even if we follow the cost-plus model, the issuer does two things apart from merely processing the payment:

- Gives credit

- Takes default risk.

When a credit cardholder pays a merchant with credit card, the merchant receives his money from the issuer bank in 1-2 days. At this point, the issuer has not received his payment from the cardholder. It sends the statement to the cardholder 30 days after the date of transaction, and the cardholder typically gets another 15 days to settle the bill. Accordingly, the total credit given by the issuer can be as high as 45 days.

If the cardholder pays the bill in full, he pays nothing for the credit. The issuer bank bears the interest cost on the card outstanding.

OTOH, if the cardholder absconds without settling the bill, the issuer bank is not made whole by the merchant. In other words, the issuer can’t recover the money from the merchant whom it has already paid many weeks before. So the issuer bank takes the risk of default by the cardholder.

As you can see, Interest Cost and Default Risk vary between $10 and $1000 transaction.

Ergo, MDR is a percentage of the transaction value and not a fixed amount.

4. Honor All Codes Rule

If a merchant chooses to accept Visa cards for payment, then, according to the “Honor All Cards” rule, they must accept all valid Visa-branded cards. In other words, merchants are not allowed to accept some Visa cards while declining others based on card type or issuing bank. This anti-discrimination rule is designed to ensure that Visa cardholders have consistent and fair access to their payment method at all participating merchants. (H/T ChatGPT)

5. Surcharge

Let’s say a consumer visits a store, picks up a product from the shelf with a sticker price of $100, and comes to checkout.

When she pays with cash, she pays $100.

If she takes out a credit card, the clerk asks for $105. The $5 is called Surcharge. Surcharge is ad valorem. The merchant receives $102.62 net (being $100 Sale Value – $2.38 MDR + $5 Surcharge).

As you can see, MDR is $2.38 whereas Surcharge is $5 i.e. Surcharge exceeds MDR.

The most egregious case of surcharge exceeding MDR that I’ve come across is Qantas. When I last checked, the flagship carrier of Australia levied 7.5% surcharge for air ticket bookings with credit card. (I’ve seen higher prices of as much as 20% for tickets booked online at BookMyShow but I’m not clear about whether Convenience Charge, as BMS calls this excess cost, can be termed as Surcharge in the credit card industry parlance.)

(The Latin term “ad valorem” means according to value. It can be part of basic amount à la MDR or in addition to basic amount à la Surcharge.)

6. No Surcharge Rule

According to the No Surcharge rule, merchants cannot penalize credit card users by charging them more than the sticker price. In other words, if the above consumer pays with credit card, the merchant cannot demand more than $100.

Contrary to what many people believe, the No Surcharge rule does not stop the merchant from giving a cash discount to incentivize cash payments. In the above example, the merchant can sweeten cash purchase by taking only $96. (It’s another story that I’ve not come across a single merchant who gives a discount for payments made with cash – or UPI or debit card).

During the last 10 years or so, the No Surcharge rule has been repealed in many jurisdictions, so merchants can legitimately charge more than the sticker price if the customer pays with credit card.

Credit Card Surcharge Update in USA:

* Banned only in 7 states

* Max 4%

* Discount on cash allowed incl. debit card

* Convenience Charge is separate and must be a flat fee, no matter the purchase amounthttps://t.co/qs7EwIIleS via @DTPaymentNews— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) October 4, 2018

7. Cap on Surcharge

As we saw earlier, Surcharge ≠ MDR and it’s often higher than MDR. Over time, as we saw above, many merchants abused the ability to surcharge, so there are new laws that cap surcharge e.g. In New Jersey, and a couple of other states in USA, Surcharge cannot exceed MDR.

Where this rule is in force, the merchant in the above example cannot charge more than $102.38 for credit card purchases (goodbye $105).

New Jersey Passes Credit Card Surcharge Bill ~ https://t.co/OtIoFc1OeA via @PaymentsDive .

MDR = Surcharge in NJ. But, in general, they need not be equal. MDR is what Bank charges Merchant and Surcharge is what Merchant charges Customer.— GTM360 (@GTM360) August 1, 2023

The above figures – normalized to Visa’s credit card ticket size of $63.00 – are depicted in the following exhibit, which also shows the workflow of a credit card transaction.

Before closing, it’s worth mentioning that, while MDR and other terms described above originated in the credit card industry, they have also been coopted subsequently by other retail payment methods like A2A RTP (e.g. UPI in India, FPS in UK, Zelle in USA, Pix in Brazil).

As of now, MDR for UPI – and almost all other major A2A RTPs in the world – is zero if the transaction is funded from a bank account (as is default), 2% if the funding source is credit card and >1.1% if it is PPI (both of which are supported on UPI).

UPI MDR is zero only on "normal UPI" i.e. where funding source is bank account. MDR for "UPI via RuPay Credit Card" is 2%. Not sure about MDR but Interchange for "UPI via PPI" is 1.1%.

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) May 4, 2023