According to the Context Matters Principle, when somebody asserts X in a certain context A, you might believe X but, when provided more context, you might change your mind. Based on the additional context B, you might

- doubt X, or

- stop believing X, or even

- start believing the opposite of X (aka ~X or X’).

Accordingly, context plays an important role in judging facts, as I’d highlighted in my blog post entitled Why Media Can’t Be Neutral.

Before doing a deep dive into this principle, let me hasten to clarify that it is not uniformly applicable to all fields. In engineering, we were taught that everything has one and only one right answer. However, during our MBA induction program, they told us that there are no right or wrong answers, only answers that work under the given circumstances. Accordingly, the Context Matters Principle is relevant only in business, economics, politics and other fields that deal with human beings and not to the realm of natural laws governing inanimate objects e.g. F=ma.

With that bit of housekeeping out of the way, Astral Codex Ten gave an excellent example from politics to illustrate the Context Matters Principle in The Media Very Rarely Lies.

In this post, I’ll give three examples from the intersection of technology and business to reinforce this principle.

1. Stripe

Payments company Stripe recently reported that AI startups have the fastest revenue run up of all categories of tech startups. The report cited a hot AI startup (let’s call it Acme AI) and said that it reached $50M Annual Recurring Revenue in two years and that no startup has achieved that feat in any other technology category so far.

Decels cast doubts on Stripe’s study by pointing out that Acme has been around for nine years, so how can two years be right.

Accels replied that Stripe’s report only mentioned the number of years it took for Acme to hit $50M ARR, not how long Acme had been in existence.

Decels hit back by saying that Acme didn’t have any revenues for seven years.

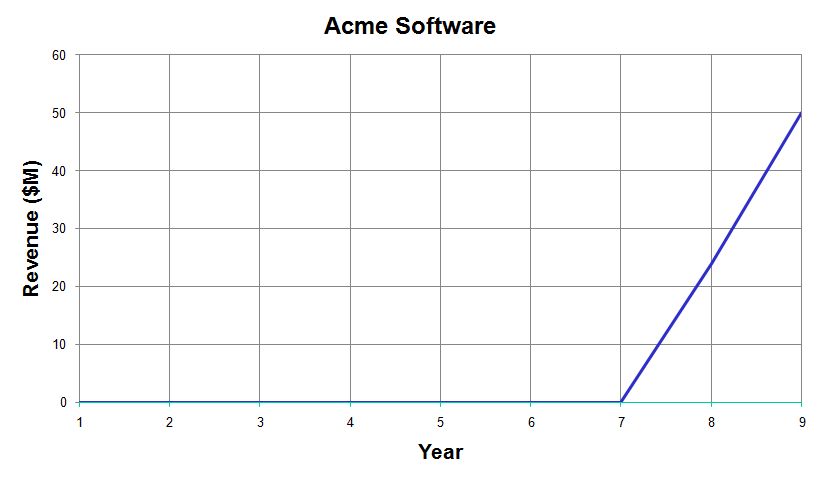

Accels countered that by posting the following chart:

As you can see, Acme had zero revenue in the first seven years of its existence and made all its revenues in the following two years.

Some people – seemingly neutral – pointed out that Stripe measured ARR based on the payments it processed for these startups. So, a startup comes on Stripe’s radar only after it starts generating revenue. Going by that, Stripe is correct in saying that Acme went from $0 to $50M in two years (year 7 to 9).

However, people who knew that Acme had not generated any revenue in the first seven years of its existence contended that the AI startup took nine years to go from $0 to $50M and pooh-poohed Stripe’s assertion.

Both sides were right.

Then somebody pointed out that Stripe measured the ARR of all startups from the first year in which they generated revenues rather than from their inception.

Then everybody realized that Stripe’s proclamation about AI startups was a statement of comparison and it’s right since it used the same yardstick for startups in all technology categories.

As we can see, with each additional piece of context, the discourse has gone from “Stripe is wrong“, “Stripe is misleading” to “Stripe is right“.

2. Uber India

Uber supports many methods of payments, including credit card, prepaid wallet, UPI, and cash.

In the beginning, I used credit card as my MOP. At the time, Uber did not charge the credit card until the start of the booking for the next ride. Click here for more details. A few years later, Uber modified the workflow and started charging the credit card at the start of the current ride. I didn’t dig this change and switched to Amazon Pay (one of the prepaid wallets supported by Uber, PayTM being the other). By far, it’s the most frictionless MOP around – at the end of the ride, Uber automatically debits the wallet with the fare displayed at the start of the ride, so it’s an example of 0-touch or “invisible” payment (but with a preknown amount).

When riders use digital payments, it takes a few days for drivers to get their dues (fare plus incentives less rake) from Uber, so drivers prefer riders who pay with cash.

However, many riders have stopped carrying cash after UPI went mainstream in India. So what happens very often is that the rider books the ride on Uber app with cash as their MOP, driver is happy to see cash on his Uber app, and accepts the ride; at the end of the ride, rider uses Walmart PhonePe or Google Pay to pay the driver’s personal account via UPI; driver sights good funds in his bank account immediately and continues to be happy.

If Uber goes by the MOP selected on its app, it’d be right in reporting that a vast majority of riders in India pay for taxi with cash.

However, people who have the additional context – most riders actually settle “cash” rides with digital payments directly with the driver without keeping Uber in the loop – would dismiss Uber’s finding.

3. Cyberscam

Every now and then there’s an article in the mainstream media saying somebody tapped a link on their phone and lost lakhs of rupees to a cyberscam.

I’m quite skeptical of such news. As a genuine payor, I know how many OTP-PIN-password hoops I need to jump through to make a payment. Against that backdrop, I can’t believe that a fraudster can siphon away money with zero – or max one – tap. I’ve suspected that, in order to boost engagement, authors of these articles resort to clickbait and conveniently skip the intermediate steps between tapping the link and actually losing the money.

That changed when I read this India Today article titled 28-year-old man loses Rs 2 lakh after downloading images on WhatsApp.

My immediate reaction was that it was one more of those sensational articles. I said to myself that the only way you could lose money by just downloading an image (and doing nothing else) is if the fraudster had used the sophisticated steganography technique and embedded a malware in the metadata of the image file. Nonetheless, I decided to read the article and clicked through the link. Imagine my surprise when I read mention of steganography in the very first paragraph of the article!

A 28-year-old man from Maharashtra lost over Rs 2 lakh after downloading an image sent to him on WhatsApp by an unknown number. The image, which appeared to be a photo of an elderly man, turned out to be a trap created using a highly advanced hacking technique known as steganography.

I no longer felt that the article was clickbait.

Going by my background in application security, I was able to figure out how the heist could happen with zero tap: After infecting the phone, a keyboard logger can monitor payments and other banking transactions done by the user, harvest the username, password, passphrase, and PIN, and use them to transfer the money to the fraudster.

When such an infected image is opened, the code quietly installs itself and gains access to sensitive information such as banking credentials and personal messages… specific tools extract the hidden instructions and execute them without raising any red flags. This allows hackers to carry out their activities without being noticed.

Assuming that the victim is not carrying out payment and banking transactions all the time, it’d take a while for the keyboard logger to harvest the credentials.The article did not specify how much time elapsed between downloading the image and the loss of the two lakh rupees. As a result, it lacked enough context for me to definitively conclude whether it’d told the whole story or not. (That said, it did provide enough context to corroborate the basic premise of its story.)

Readers seldom state their context expectations upfront.

As a result, writers can never be sure if the context they’ve provided is enough to insulate them from the charge of their content being biased, clickbaity, etc. Furthermore, how much context is enough context depends on demographic and cultural factors like the audience’s IQ, reading comprehension chops, shrinking violet index and tolerance to caveat emptor.

However, at the minimum, writers need to provide at least as much context as their story is predicated upon. In other words,

- They may skip the additional contexts that their story does not rely on.

- They may not skip the additional contexts that their story does rely on.

I’ll let readers decide which of the three examples above belong to which of the two situations – and judge for themselves whether Stripe, Uber, and India Today were justified in omitting the additional context.