In Why Is It Hard To Catch Cybercriminals?, we took the following example of a cybercrime:

Joe pays Jane online for something and does not receive what he was promised.

We then saw why it was hard to catch the cybercriminal (Jane in this case).

In this second part, we will examine who is liable for cybercrime.

Cybercrime goes beyond the anonymous nature of cash and non-anonymous nature of digital payments. That’s because:

- Cash transactions cannot happen remotely. So, Joe needs to meet Jane in person to hand over the cash to her. While cash is an anonymous MOP, Joe does know the identity of Jane. Besides, if the meeting happens in a public place, Jane is captured in many CCTV feeds.

- Digital Payment introduces many intermediaries such as Payor Bank, Payee Bank, Scheme Operator, and so on. While these entities follow the law, it’s not like laws related to this specific scam are the only laws they’re governed by.

As we can see, in the context of cybercrime, cash is not all that anonymous, and the non-anonymous nature of digital payments is not all that helpful in solving cybercrimes carried out via an A2A RTP.

While referring to Jane, I prefixed the term “scammer” with “alleged”. That’s because of the following reasons:

- In any citilized nation, Jane is innocent until she’s tried and found guilt by a court of law.

- What’s the guarantee that the alleged victim Joe is telling the truth? Imagine a customer who pays you for work you’ve done for them, then develops cognitive dissonance / buyers remorse, approaches cyberpolice and files a fraud complaint against you? Will you part with the money readily?? (In a credit card payment, this would be called “first party fraud” but, for reasons we’ll see shortly, that term does not exist in A2A RTP.)

The thief obviously is culpable for cybercrime. But, as we saw earlier, it’s not easy to catch her.

Ergo it’s human nature – and the founding principle of the so-called “drunk under lamp post” regulation – to stick it to somebody else who can be caught easily.

TIL:

Drunk Under Lamp Post Effect aka Streetlight Effect: Search for something where it's easy to search, not where you lost it.

(H/T @matt_levine)https://t.co/IkGkldZogd.#Drunk #Keys #Streetlight #Park— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) March 9, 2022

In India, going by outrage on social media, the pet whipping boy is the Payee Bank. People want to hold Jane’s bank responsible on the ground that it opened an account in the name of the Alleged Scammer despite doing KYC. They seem to assume that KYC is character certification. But it’s not. As long as you produce the necessary KYC documents, a bank is not under any obligation to vet your character before opening an account in your name (Not legal advice.)

In fact, banks give loans even to convicted criminals and cannot be expected to deny a basic bank account to an alleged criminal like Jane (Not legal advice.)

In fact, banks give loans even to convicted criminals and cannot be expected to deny a basic bank account to an alleged criminal like Jane (Not legal advice.)

In the UK, in a fit of populism (IMO), the regulator ordered (payor) banks to reimburse all victims. Banks said no and rejected 90% of the claims. At the height of hysteria, the payment system regulator wanted to call this a matter of national security. Things have cooled down now.

In USA, the payor is left to his own devices against cybertheft.

“Drunk under Lamp Post” logic breaks down in the case of cybercrime because it involves a number of parties other than banks such as the Telecom company that provides mobile connectivity to the Alleged Scammer, the electricity company that provides electricity with which the Alleged Scammer charged her phone, and so on.

It’s obviously not possible to hold all of them culpable.

By the same token, it makes no sense to hold banks responsible, either.

Even if the Scammer received monies into a KYCd bank account and used a KYCd mobile phone connection to run this scam, this is between Scammee and Law Enforcement. Not legal advice but I don't see how the Bank and Telco have any liability. pic.twitter.com/IOdFdec0vB

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) February 13, 2022

I’m aware that banks, money transfer operators and many other financial institutions are required by law in many jurisdictions to block terrorism-related payments and file Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) / Suspicious Transaction Report (STR) for terrorism related transactions. They fulfill that responsibility by using sanctions-screening software and FATF databases. But I see no way for them to block fund transfers related to all kinds of crimes including APP scams.

I wish there was a more pleasant way of putting it but the payor is inevitably the only person left holding the can for a cybertheft carried out via A2A RTP. At least until the cops nab the payee and recover the money from her after due legal process.

Zelle makes this point explicit. The #1 A2A RTP of USA warns people upfront not to use Zelle to make payments to people they don’t know or trust.

Consumers should only use Zelle® to send and receive money with friends, family, and businesses they know and trust (Source)

Zelle also makes a crystal clear distinction between Fraud and Scam.

- Fraud is Unauthorized Payment i.e. when someone has stolen your ID / bank credentials / credit card info and made a payment without your authorization.

- Scam is Authorized Payment i.e. when the Scammee aka Mark has made the payment, just to a wrong person or for the wrong purpose, or both.

While Joe might feel defrauded, there’s no fraud – it’s a scam.

Zelle mentions clearly that the payor may not be able to get their money back in the case of a Scam.

While New York Times makes a lame attempt to stick it to banks in a recent article, I found the following comment apt:

Zelle is cash. If you hand your cash to a fraudster it’s your problem. Don’t expect less foolish users to effectively subsidize your mistakes by putting the culpability on the banks, their responsible customers and their shareholders. When you hit send, you have released the cash. That is that. That’s why you have to make a choice TWICE. If you don’t trust yourself to handle your finances, get help.

Harsh as it might sound, it’s difficult to disagree with this take.

My unsolicited $0.02 to other regulators and scheme operators:

Use the Zelle playbook to make it clear that the payor owns A2A RTP Scams.

Had Joe made the above payment with a credit card, he’d have gotten his money back quite easily.

Credit card provides a wide range of protection for consumers:

- Fraud aka Unauthorized Payment: Someone else uses my credit card to make purchases for themselves.

- Scam aka Authorized Payment: I use my credit card to make a purchase. I don’t get the product.

- Deficiency of Service: I use my credit card to make a purchase. I get the product. But it does not work as advertised.

According to credit card network rules, when Joe contacts his bank after realizing that he has been scammed, his bank should reverse his charge, pending a chargeback / dispute investigation. In some jurisdictions (e.g. USA), the process is fairly seamless, and Joe will get his money back with a single call. In some others (e.g. India), which use 2FA for credit card payments, the bank will pushback on the credit cardholder, saying “only you know PIN / OTP, so you only must have made the payment”. However, even in these markets, Joe will eventually get his money back, just that it will take more effort than a single call.

The best way for consumers to protect themselves from scams and frauds is to pay with credit card.

If that’s not possible for whatever reason, consumers should exercise extreme caution while initiating a payment with UPI, FPS, Zelle or any other A2A RTP. As we’ve seen, once you send money out from your bank account with an A2A RTP, it’s extremely difficult to get it back. Better to be safe than sorry, and all that…

The common man might crave for A2A RTP method of payments to support the same degree of scam and fraud protection as credit card. But that’s like expecting a Maruti 800 to be a BMW.

As I’ll explain in a follow-on post, Scam / Fraud protection is a feature in credit card but a bug in A2A. Unfortunately for A2A RTP users, it’s not easy to fix the bug without alienating merchants and threatening the very existence of the payment method itself.

Quora Link: https://qr.ae/pG3YDo.

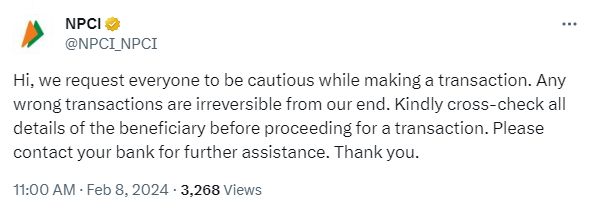

UPDATE DATED 8 FEBRUARY 2024:

Wish fulfilled!

NPCI, the operator of UPI, among other retail payments rails in India, follows the Zelle playbook and makes it crystal clear that UPI payments are irreversible aka irrevocable.

Of course, readers of this blog already knew that years ago!