As soon as the UK government announced that it won’t accept CoWIN Certificate as proof of vaccination of Indian travelers, all hell broke loose on Twitter.

Some people argued that CoWIN portal provides cloud-based, digitally signed vaccination certificate.

UK cannot make sense of India's CoWin vaccine certificate, because India's QR coded, digitally signed document is light years ahead of Britain's handwritten memo. Tough to swallow the pill from natives.

— Sreemoy Talukdar (@sreemoytalukdar) September 22, 2021

Well, CoWIN Certificate may do all that but they totally miss the point: If Britain’s systems are light years behind, then it obviously can’t make sense of CoWIN certificate.

Some others don’t realize that the real aspersion cast by UK is on the paper certificate.

If UK govt can access CoWIN, I agree. Else aspersion is cast on person claiming to have CoWIN paper certificate, which can be easily photoshopped, and not on CoWIN itself.

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) September 22, 2021

Some people forget that, when Indians travel to UK, it’s incumbent upon India to go the extra mile to issue a certificate that UK immigration can decipher.

And why will they stand in a line to learn about CoWIN? Are they the ones trying to enter India??

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) September 23, 2021

Overall, there was a lot of faux patriotism from the Twitterati but little evidence that the average tweeter really understood the crux of the issue:

It’s not Faux Patriots sitting in India but but some immigration officer in a foreign country who needs to look at the certificate and verify the vaccination status before waving the traveler through.

Having passed through immigration checkposts in dozens of countries countless times, it’s the whim of the immigration officer behind the counter that really counts.

Thankfully, the outrage died down quickly. I don’t know if it’s correlation or causation – or merely coincidence – but I sensed normalcy return soon after Economic Times published this op-ed by Mr. Ram Sewak Sharma, the Chairman of CoWIN Panel.

In this piece, Mr. R S Sharma gave an excellent overview of CoWIN and future plans for the portal.

I’d given a shout out to CoWIN for being frictionless last month.

Happy 75th Independence Day!

Freedom from friction!!

Friction in websites and apps!!!

Not only in the PayTMs & Swiggys developed by well funded startups but even in the volunteer-built govt ones like https://t.co/ZhvYo4beuZ, CoWIN, etc.— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) August 15, 2021

After reading the op-ed, as an Indian IT industry lifer, I was proud to know that CoWIN also incorporates state-of-the-art technology and conforms with internationally-accepted specifications.

That said, there are many open questions about the usability of the CoWIN Certificate for the purposes of travel.

#1. QR DOES NOT WORK

Typing a URL on a smartphone virtual keyboard can be a PITA. QR solves that problem by letting you scan the code and reach a webpage without having to type its URL.

When people see a QR, they simply scan it. If nothing happens after that, they will call it a #FAIL and move on.

That’s the case with the QR code on CoWIN certificate – nothing happens when you scan it.

There’s a fineprint on the certificate suggesting that people need to type http://verify.cowin.gov.in before scanning the QR.

When I visited that page on the CoWIN portal, I found no mention that I should follow the instructions given on it with a smartphone. While some people claimed on Twitter that the verification instructions work equally well on a desktop, that was some more of faux patriotism. It didn’t work for me even after several attempts. I didn’t even get the error message that was supposed to appear if the QR failed to scan after 45 seconds.

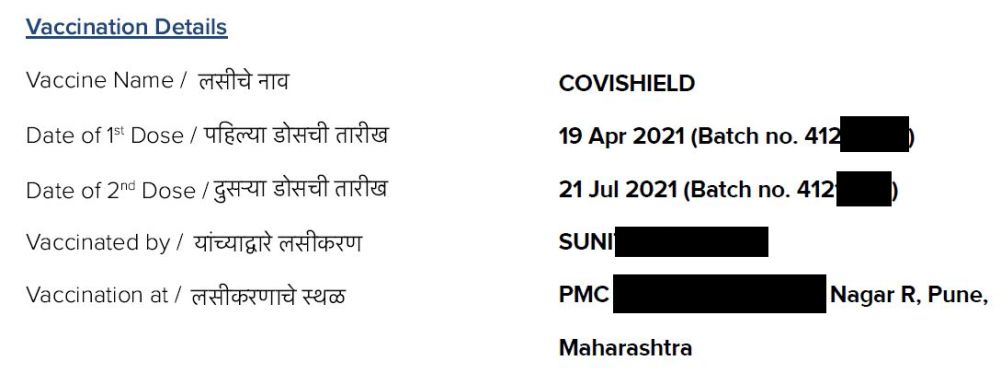

I then typed the URL on my smartphone browser and visited the page. This time, I was able to scan the QR and get the proof of vaccination (shown at right). (It had a yawning gap. More on that later.)

I then typed the URL on my smartphone browser and visited the page. This time, I was able to scan the QR and get the proof of vaccination (shown at right). (It had a yawning gap. More on that later.)

I’m sure CoWIN knows that asking people to type a URL on a smartphone goes against their experience with QR codes in general and runs counter to internationally accepted specifications of how the QR technology works.

Since it’s still insisting on this step, there must be a good reason. If it’s to comply with WHO, DDCC:VS, W3C et al, then CoWIN should make it clear that it has introduced a friction hotspot in order to conform with international standards.

My $0.02: CoWIN should print the logos of these international specifications organizations on the certificate. That would act as a “Seal of Trust” and encourage widespread use of the verification feature on the CoWIN certificate, especially by foreign governments who could otherwise dismiss the QR offhand with a “it doesn’t work” remark, and deem fully vaccinated CoWIN Certificate holders as unvaccinated.

#2. ITVC

From the op-ed:

“CoWIN plans to release an international version of the vaccination certificate for travel purposes. Citizens will soon be able to log into the CoWIN portal and apply for an International Travel Verification Certificate. An ITVC will soon be available for download in various internationally accepted formats, including WHO’s DDCC:VS, the Europen Union’s digital Covid certificate (DCC), and the International Civil Aviation Organization’s visible digital seal (VDS).”

The need for a separate artefact like ITVC suggests tacit acceptance that the present CoWIN Certificate is not fit-for-purpose as proof of vaccination. Well, isn’t that what the UK government said in the first place?

Alas, it now appears that even fully vaccinated Indian travelers will face quarantine in UK – and other countries with similar rules – until ITVC becomes a reality.

#3. INCOMPLETE INFO

The final certificate that’s downloadable as a PDF from the CoWIN portal mentions the doctor and hospital details only for the second jab. (Well, if you wish to pick a nit, it does not explicitly link them with the second jab but I know that these details pertain to the second jab). Similar info is conspicuous by absence for the first jab.

On top of that, the webpage that shows up after scanning the QR successfully does not provide any information about the first jab.

I’m sure that’s unintentional but it could appear to an immigration officer that the certificate is trying to hide something about the first jab. Obviously, that’s not a great way to foster trust, especially among an audience that has already expressed its skepticism.

My $0.02: Either this info should be provided for both jabs or it should be removed from the CoWIN Certificate altogether.

These issues raise questions about the credibility of the present CoWIN Certificate for purposes of travel.

I’m glad that the CoWIN Panel has sensed this and is working towards a swift resolution of the open issues.

In a larger context, this is about reports in software. Given that CoWIN Certificate is a report from the CoWIN software, this episode highlights the need to design reports and dashboards such that they work for the user for whom they’re developed rather than the product manager who develops them.

Of course, this is common sense. But, as the saying goes, common sense is not very common!

PS: A condensed version of this blog post appeared in my letter to the editor of the Economic Times on 27 September 2021.