Consumers tell you in surveys and focus group studies what features they want in your product. You build a product with those features. Consumers don’t like them. Your product bombs.

In consumer behavior, there’s often a disconnect between what consumers say they want and what they actually like.

In Why Do People Obsess Over Security And Then Make Payments Without A Password?, we saw a stark version of this disconnect: Consumers say they want their payment apps to be secure but overwhelmingly like frictionless payment apps that throw security to the wind.

In this post, we will give two examples of the disconnect and speculate on the reasons behind it.

EXAMPLE 1: OVERDRAFT PROTECTION

Once in every few years, there’s an outrage over overdraft protection fees in the US banking industry.

For the uninitiated, here’s a working definition of overdraft protection, courtesy Stanley Bing / @thebingblog.

“No matter what you spend with your debit card, even if you have no money in your account, the guys at the bank will make sure that you’re not embarrassed. They’ll pay your tab!”

For providing this service, banks charge a fee called Overdraft Protection Fee. It’s typically $35 per incident of overdrawing. If customers are not careful, they could easily rack up a tidy sum in overdraft protection fees every month. Overdraft Protection happens to be a major source of revenues for American banks.

Some foreign banks have started covering overdrafts in India. It’s a matter of time before customers start noticing the charge levied for this service and spark off a similar outrage even in India.

How common is "overdraft protection" in the Indian banking industry? TIL that at least two Top 5 pvt sector banks in India offer this facility – called Temporary Overdraft – and, that too, without any fees. https://t.co/yErKeS2MjW via @GTM360

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) March 14, 2019

During the Great Financial Crisis, consumer advocates ranted that banks forced overdraft protection upon consumers just so that they (i.e. banks) could make money.

To appease consumers, in 2013, the US government passed Reg. E, which mandated that banks must get explicit opt-in from consumers for overdraft protection.

As I predicted at the time to my retainer clients, banks went to their customers to get the required opt-in (see my blog post entitled Overdraft Protection – Another Hot Opportunity For BPO).

Tens of millions of Americans opted in, probably because it’s cheaper to have banks cover overdrafts even at thirty five bucks a pop instead of missing payments to utilities, suffer service disconnections, and incur much higher costs to get the connections reinstated.

Seven years later, US Banking industry’s overdraft protection revenues have bounced back to 2009 levels.

Going by this screen, Airtel Payments Bank has obtained the required consent for opening an account. For a digital bank, a check in the box and tap of I AGREE button should be sufficient proof of "informed consent". Nobody's going to explain fineprint face-to-face. pic.twitter.com/OKdbjZkOWs

— GTM360 (@GTM360) April 30, 2019

Seeing this, consumer advocates have sparked off another round of outrage. They’re now claiming that banks are “tricking consumers” into opting-in for overdraft protection services. (Yes, I’m looking at the recent lawsuit filed by CFPB against TCF National Bank).

IMO these rants are groundless and deserve to be be dismissed summarily. Banks levy overdraft protection fees ONLY when opted-in consumers make purchases with their debit card or check without having enough money in their bank accounts, NOT because they opted in for overdraft protection. Per se, it shouldn’t matter how the opt-ins were obtained.

EXAMPLE 2: GOOGLE MAPS DRIVING TIME

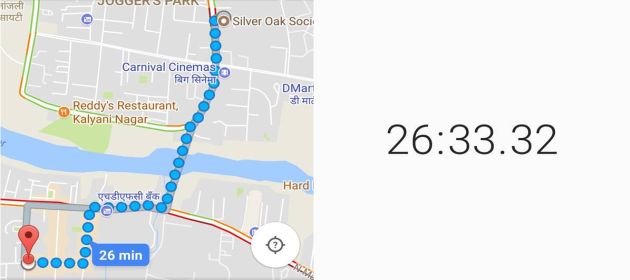

In the FORTUNE magazine article entitled Google and the Rest of the Tech Industry Are Grappling With These 3 Data Problems, Google’s chief economist Hal Varian explained the challenge faced by Google regarding data and privacy thusly:

People say they want privacy but their actions indicate that they don’t really care about it. Although many people say they dislike companies tracking their locations, everyone loves the feature of Google Maps that tells you how long it will take to get home.

As you can see, there’s a clear conflict between want and like in this case.

WHY THE DISCONNECT?

We’ll now speculate on the root cause of the disconnect between what consumers say they want versus what they actually like.

It’s quite straightforward in the first example and a bit nuanced in the second.

EXAMPLE 1: OVERDRAFT PROTECTION

Let’s decompose overdraft protection into benefit and cost.

Benefit: Your tab will be covered if you have zero bank balance.

Cost: $35

The root cause of the conflict between want and like is quite obvious: Consumers think the cost is a ripoff.

This might seem contradictory to the thought process they exhibited when they opted-in for overdraft protection. But look at it this way: When they opted-in, both Overdraft Protection Fee and Reinstatement Charge were theoretical. But when they actually overdrew their account, the Overdraft Protection Fee became real whereas the Reinstatement Charge remained theoretical. That’s because the bank covered the overdraft, so their payment to utility company went through and their service was not disconnected.

Their outrage against Overdraft Protection Fee is driven by the real cost they incurred, however much lower it is than the theoretical cost they didn’t incur.

If US banks allowed unlimited overdrafts for a single flat fee of $35, there won’t be so much debate around overdraft protection fees.

— Ketharaman Swaminathan (@s_ketharaman) November 4, 2009

EXAMPLE 2: GOOGLE MAPS DRIVING TIME

Let’s parse Hal Varian’s statement into feature and benefit.

Feature: Location tracking.

Benefit: Know how long it will take to get home.

It’s obvious for the Product Manager that the feature is required in order to deliver the benefit. However, that’s not the case for consumers. I can see three patterns of consumer behavior:

- Some consumers don’t make an association between the benefit and the feature. They like the benefit. They don’t like the enabling feature. In their mind, there’s no disconnect.

- Some other consumers know, like Google, that the benefit requires the feature. They like the benefit. They don’t like the enabling feature. They sense the disconnect. But, by opting for the benefit and continuing to complain about the feature, they’re exhibiting irrational behavior, as Varian hints.

- The remaining consumers also know that the benefit requires the feature. They like the benefit. Whether they like the enabling feature or not, they’re willing to accept it as the cost of enjoying the benefit. But, being the most sophisticated of the lot, they see a disconnect in the “tenure” of the cost: They have use for the benefit once or twice a day and resent the need for the feature to be activated all through the day. That is, they want to know how long it will take to get home once or twice a day but protest against location tracking by Google for the entire day.

We have seen the conflict between what consumers say they want and what they really like.

We’ve also speculated on a couple of reasons for this conflict. Actually, there’s really nothing rocket science about it: It’s a nod to the good old human behavior trait of desiring the fruit without the labor.

It’s evident that product managers and marketing managers need to decode this want-versus-like disconnect or risk seeing their branding and sales efforts go down the drain. In a follow-on post, we’ll provide some guidance to help them with this pursuit. Watch this space!