There’s a lot of buzz in the media about how delays in realizing payments are making life difficult for vendors selling servers, laptops, tablets and other IT hardware to the government. Click here to see a recent article on this topic.

There’s a lot of buzz in the media about how delays in realizing payments are making life difficult for vendors selling servers, laptops, tablets and other IT hardware to the government. Click here to see a recent article on this topic.

While the industry is aware that government generally takes longer to settle invoices than the private sector, apparently not many suppliers are willing to accept DSOs that exceed 730 days (i.e. 2 years) of late. As a result, some vendors (like Zenith) have pulled the plug on government business.

While they might be right in their actions, this took me back to a time when I used to work for an IT company that faced a similar challenge. For exactly the same reason cited by an executive from HCL Infosystems in the above article – “The government is the biggest buyer of IT products and services” – staying out of the government business was simply not an option for us.

Therefore, it was down to me and a few of my colleagues to huddle together and devise a new strategy for making money from government contracts. As soon as we sat down to work on this mission, we spotted a few attributes that were common to almost all government procurement scenarios:

- Shipments are made to end users located in multiple locations over an extended period of time.

- However, the vendor needs to submit a single invoice for the entire contract to a central payments authority, which is several layers removed from the actual end users. And, generally, the twain doth not meet

- Delivery takes place 5-6 months after tender opening.

When we examined how our company was geared up to respond to these harsh realities of government business, we saw a dismal picture.

We discovered that our invoicing used to get delayed – or, in the worst case, missed out – whenever staggered shipments were made to different locations. We resolved this problem by enhancing our accounting software such that it tracked multiple partial shipment delivery notes and automatically recognized complete fulfillment of the order and generated the invoice without any manual intervention.

Because of attribute #2, it was not possible for our debt collectors to chase up for payments with the customer’s central payment authority by physically pointing out to the goods as proof of delivery and installation. Only documentation talked. That too anal-retentive level of documentation. Receiver’s signature must be on the LHS of the delivery note. Organization’s seal must be on the RHS of the hardware installation report. If they were interchanged, sorry, no payment.

We tried many ways of perfecting our documentation. In the end, what worked was for the salesperson to travel in the delivery truck and get all customer acknowledgments in the prescribed manner. It was extremely important to do this as the goods were being delivered, not the next day or even one hour later. For an end user in a remote place in a government organization, receiving a computer was akin to a child getting candy. You must capitalize on the euphoria when it happens, or it’s lost forever.

Initially, many sales guys (and gals) protested about doing this “menial work”. But all their objections vaporized when they found out how “chaperoning” deliveries expedited collections and helped them receive their sales commissions faster (of course, this presupposes the existence of a robust enterprise incentive management system like this one, but that’s a topic for another day).

As for the third attribute, it looks like nothing much has changed in the government procurement process. As one of the vendor executives interviewed in the aforementioned article says, “Companies commit to a price on day one but deliver about 180 days later”.

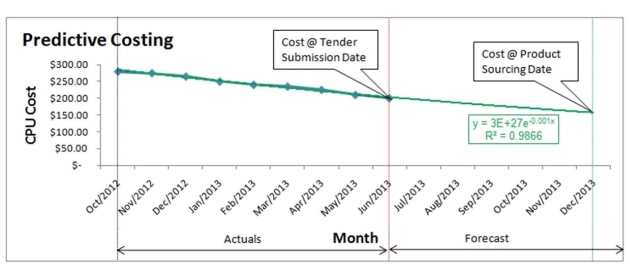

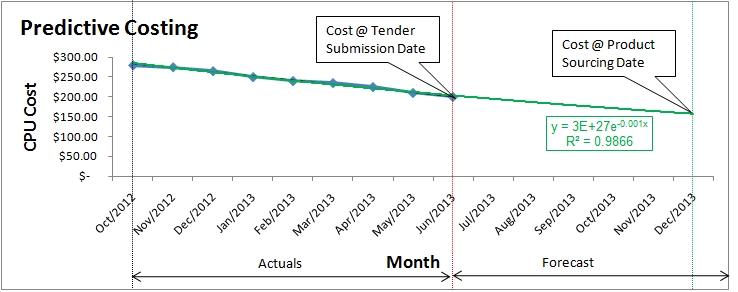

While this sounds like a challenge, it’s actually a great opportunity in the IT hardware industry where component costs are deflationary. If a certain CPU – an integral part of a computer – costs (say) US$ 200 on the date of submission of the tender, its sticker price would inevitably drop to (say) US$ 155 by the time it needs to be purchased. Future cost of the CPU can be predicted by carrying out a regression analysis based on historical costs, like we did at the time.

From this predictive costing model, we were able to predict the future cost of many components (think RAM, hard disk drive, monitor, keyboard) with more than 98% confidence.

By recomputing selling prices based on reduced component costs, we were able to secure higher margins on government contracts.

Of course, this is not possible in private sector deals where quote-to-delivery cycles are much shorter (typicaly 2-4 weeks) and component cost reductions are therefore insignificant.

While exchange rate risk can throw a spanner in the works when raw materials are imported over an extended period of time, this risk can be mitigated by using currency hedging strategies.

More on this approach can be found in our case study titled MENA Distributor Grows Government Sales Sharply.

While technology business from the government is fraught with challenges, it’s still possible to execute it profitably. What it takes is a fresh look at your “Quote-to-Cash” process spanning configuring, pricing and quoting through to delivery, invoicing and collection.