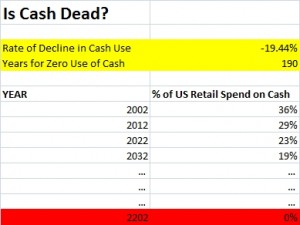

According to a Barron’s article titled The End of Cash?, the use of cash as a percentage of retail spending in the USA declined from 36% in 2002 to 29% in 2012. That works out to a CAGR of -19.5% per decade. Extrapolating these figures, cash usage should become 0% by 2202. That’s 190 years from now. Please click here to download the Excel model used to arrive at these figures.

According to a Barron’s article titled The End of Cash?, the use of cash as a percentage of retail spending in the USA declined from 36% in 2002 to 29% in 2012. That works out to a CAGR of -19.5% per decade. Extrapolating these figures, cash usage should become 0% by 2202. That’s 190 years from now. Please click here to download the Excel model used to arrive at these figures.

Cash still accounts for 40% of P2P payments (Source: Blog post titled The Less-Cash Society by Aite Group’s Ron Shevlin). If I factored P2P into my model, it will drastically push out my Zero-Cash-Day prediction of 2202. But, since it’s fashionable for everyone and his dog to proclaim that cash is dead, I’ve conveniently ignored P2P.

But will cash really be dead even two centuries from now? I strongly doubt it.

Mainly because the movement between cash and noncash modes of payment is not as unidirectional as it is often made out to be.

Just as electronic fund transfers and card payments have been replacing cash in some facets of life, cash has also been edging out electronic payments in some others.

Counterintuitive as this might seem at first glance, a quick look at a few recent payment innovations will make my point clear.

A couple of years ago, we saw the launch of Kwedit in the USA. Now called PayNearMe, this alternative payment method permits people to shop online but pay with cash at brick-and-mortar stores. As I’d pointed out in Why Pay By Credit When You Don’t Have To Pay By Kwedit, a blog post I’d written at the time Kwedit was launched in 2010, the new method of payment was targeted at people who either couldn’t qualify for payment cards or didn’t want to use them for making online payments owing to security concerns.

Subsequently, growing incidents of identity theft and loss of financial data have prompted regulators to enforce greater security measures by way of 3D Security, One Time Password, Out of Band Authentication and so forth. While they’ve made online payments more secure, they’ve also made them more rare: The friction they’ve caused has virtually obliterated the mobile payment channel; the multi-website trips they entail before a payment can be completed have led to greater number of failed online payments, which could be as high as one in 12 payments, as I’ve noted in my blog post titled Skating Away With Online Payments. Of late, the fear of an online payment getting lost somewhere in the cyberspace is increasingly pushing me to opt for cash-on-delivery terms for eCommerce transactions despite having used card and bank transfer based electronic payments regularly for around 10 years now. So, at least in my case, ‘once an electronic payment user’ doesn’t mean ‘always an electronic payment user’.

Looks like I’m not alone.

A leading airline in India recently announced cash-on-delivery as a new way to pay for customers booking tickets on its website. COD is unprecedented for flight tickets, which could hitherto be booked only against online payments via bank transfers and debit / credit cards.

Under this airlines new COD mode, customers browse flights, check availability and book e-tickets online, same as always. However, they don’t make any payment at this stage. Nor do they receive the e-ticket at the end of the session. What happens is, the airline’s COD service provider – a Silicon Valley VC-funded startup – visits the customer’s house and collects cash. As soon it confirms the receipt of cash, the airline emails the e-ticket to the customer.

With this great example of omnichannel journey, the airline mitigates the risk of online payment-holdouts moving away to costlier physical outlets to buy their tickets. At the same time, the new payment method doesn’t erode the airline’s margin since cash collection charges are no greater than the Merchant Discount Rate / Merchant Service Charge applicable for card payments.

If cash can enter e-ticketing, a business that has always worked on online payments, cash can enter any business. I’m totally convinced about my oft-expressed belief that the cash-versus-cashless pendulum could swing both ways.

So, at least for now, tales of the death of cash are, like those of Mark Twain’s, greatly exaggerated.