Many discussions on security standards emphasize how Chip + PIN and Two Factor Authentication reduce fraud loss and exhort countries using Magstripe / Chip + Signature and Single Factor Authentication (e.g. USA) to immediately migrate to the newer technologies. Take for instance the Finextra article entitled Campaign pushes for US adoption of chip and PIN.

Many discussions on security standards emphasize how Chip + PIN and Two Factor Authentication reduce fraud loss and exhort countries using Magstripe / Chip + Signature and Single Factor Authentication (e.g. USA) to immediately migrate to the newer technologies. Take for instance the Finextra article entitled Campaign pushes for US adoption of chip and PIN.

All these urgent missives totally miss one thing: Merchants and banks make revenues only when the transaction is successful, not when it’s blocked for being potentially fraudulent. In other words, mitigating fraud does not pay the bills.

I’m not for a moment suggesting that merchants should not make attempts to mitigate fraud or that they should throw caution to the winds. But I’m imploring regulators to remember that an obsession with eliminating fraud could throw the baby out with the bathwater by killing sales and causing massive customer dissatisfaction.

This is because virtually every security measure designed to prevent fraud creates collateral damage by way of increased friction viz. need to remember the PIN in the case of an offline Chip + PIN transaction.

Security pundits have been claiming for years that there are ways to implement security without compromising on convenience. But merchants haven’t seen too many implementations of such technologies in the mainstream market to take these claims seriously.

For at least a decade, we’ve been hearing about the next great security technology that will crack the Holy Grail of convenience versus security. Hasn’t happened in the last 10 years. Doubt if it will ever happen unless we drastically change the way we think about security technologies.

In simple terms, the security challenge is as follows: User wants easy access to her funding source to make a payment. User wants others to have absolutely no access to her funding source to make a payment. The “system” needs to figure out whether user is the legitimate owner of the funding source (and accordingly offer the easy access to her) or not the legitimate owner of the funding source (and deny access to her). But the system can’t see the user physically and can’t figure out whether she is genuine or not. The way current security technologies are designed, the only way the system can do what’s expected of it is to subject ALL users to the same degree of gatekeeping aka security, which causes inconvenience to everyone. Some people will tolerate the inconvenience and attempt to complete the payment at all costs. Some others will simply ditch the purchase. I may be daydreaming but I think this Holy Grail will be cracked only when we think beyond authentication factors and have a technology that changes the present paradigm of “presence”.

Customer tolerance to the incremental friction caused by incremental security needs to be seen in the context of many factors specific to local culture and business practices.

If consumers have only one card, remembering just one PIN number is not such a big deal. However, if they use multiple cards regularly, they need to remember multiple PINs, which poses a lot of friction. (Most probably, people in the latter category would write down all their PINs on a piece of paper and keep it inside their wallets, which would defeat the basic purpose of security.)

Recourse Against Fraud

In some countries (e.g. USA), when a cardholder spots a fraudulent charge on their credit card statement, they can report it to their bank and have it reversed immediately. The bank carries out the chargeback investigation behind the scenes. As a result, it’s simple for them to seek recourse against fraud. Compared to that, the need to remember a PIN – or many PINs – would be painful. Their tolerance to friction is low.

On the other hand, in some other countries (e.g. India), a cardholder caught in a similar situation gets shunted around between the issuer, acquirer and the merchant. So seeking recourse against fraud is not so simple for them. Therefore, they might be willing to jump through a few more hoops while making the payment. Their tolerance to friction is high. If the regulator insists on stringent security measures like two-factor authentication, consumers may still try out digital payments. But if the additional hoops lead to failure of payment because of loss of Internet connectivity or outage of one of the systems in the chain, their enthusiasm wanes with time and they go back to other forms of payment that carry less risk of failed payments.

The impact of friction is two fold:

- Customer abandons the transaction and the business suffers a loss of revenue, or

- Customer completes the transaction with an alternative method of payment viz. cash. Let’s assume that the merchant suffers no net cost impact in this case since the incremental cost of cash handling could be offset by the savings on credit card processing fees.

So, while steps taken to mitigate fraud could lower fraud loss, they could also crimp revenues. This has to be kept in mind before any new payments security technology can hope to achieve mainstream adoption.

Therefore, any discussion about payment security is complete only when it addresses both

(A) Fraud loss as % of Sales, and

(B) Revenue loss as % of Sales.

In the migration from magstripe / Chip + Signature to Chip + PIN for offline payments, it’s too early to predict which of these two metrics will prove decisive.

But, in the related case of online card payments, it appears that fraud loss is not as big a concern as revenue loss owing to friction, given how leading merchants like Amazon have still not implemented 2FA (VbV / MSC / OTP) despite the fact that FFIEC issued guidelines for 2FA way back in 2005 and renewed them in 2012.

I’m not alone in advocating a balanced approach towards payment security.

I’m not alone in advocating a balanced approach towards payment security.

“The challenge is friction from a checkout point of view. If merchants are looking for security perfection, then they are going to be turning away good sales.”, says George Peabody, a partner at Glenbrook Partners here. “When you are doing checkout out of a merchant’s shopping cart − particularly on a mobile device − it is really important to be as friction-free as possible”, he adds.

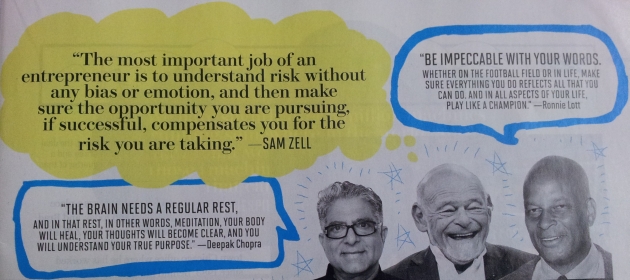

End of the day, it all boils down to how a business treats the risk of fraud loss. If it follows the advice of Sam Zell (pictured in the exhibit on the right), the famous American real estate magnate and private equity investor, it would accept the risk if the returns outweigh it. If not, it would hurtle towards “zero sales, zero fraud” end state.

Neither choice has nothing to do with whether its security technology is new or old.